Zach Thomann,Sports Editor

After the sectional finals are over, many wrestlers wait until the next season. For Hunter Richard, his journey as a wrestler hasn’t stopped since seventh grade at Holland Patent High School, and will continue after senior year.

The journey only goes farther in the off season, where Hunter is on the road competing in tournaments across the country. This puts Hunter and his father, John, in a hotel almost as much as they are at home.

From the time Hunter could walk, John has been conditioning his son to excel in the family sport that he’d been passionate about for years. The goal was uncertain, but with three New York State wrestling championship titles and a full scholarship to Cornell University, Hunter has not fallen short of John’s expectations.

The Holland Patent wrestler has been covered by plenty of news outlets for his abilities as an athlete accompanied by the coaching tactics of John, but the life at home for the Richard family is an anomaly as well.

John Richard has found a way to keep a good relationship as a father and coach with Hunter in a sport that is arguably hard to do.

Building A Relationship:

“Flipping the switch” between a parent and coach is what complicates the athlete’s relationship at home, according to SUNY Brockport sports psychologist professor Dr. Stephen Gonzalez.

What he means by a figurative switch is which boundaries are set in place ahead of time so a child can recognize when a parent is being a dad or a coach.

In the case of the Richard family, John has been a head coach longer than Hunter has been alive. This makes it challenging for John to show his son which persona is speaking when being a coach is a big part of his life.

In many cases, the switch between parent and coach at home is as simple as John saying, “I’m talking to you as a coach.” Other situations aren’t as clear for John. One in particular, is a story he claims to tell all the time.

When Hunter was in seventh grade and beginning his varsity high school career, John thought it was important to send a message to the team and his son that nobody will get special treatment. After a long practice where Hunter was scrutinized by coach Richard, a question fluttered at the family dinner table about how wrestling was going.

As a soft-spoken kid, Hunter failed to answer.

“Coach Richard was an asshole today,” John said.

John isn’t always direct with his methods, but he made it clear to his son which persona was in the room. With the help of his wife, Gina, their son has been put in the position to be successful later in life.

As teachers in the Holland Patent School District, John and Gina value the importance of supporting Hunter with anything he does in life. They believe that Hunter wouldn’t be at the position he is in as a wrestler and student without the excessive support of his parents.

“Talent can only get you so far without the financial support,” John said.

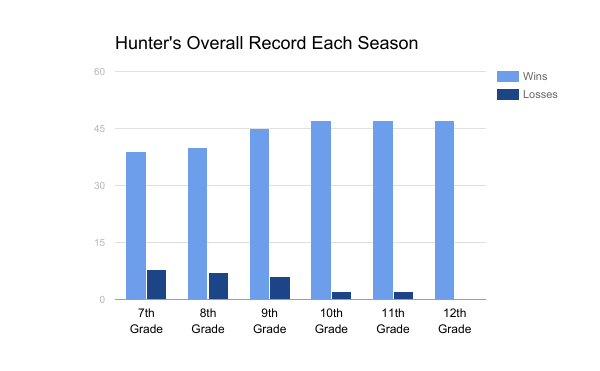

Outside of school events, Hunter has traveled across the country and the world, making trips as far as Finland, Estonia and Amsterdam. This has helped him reach an overall record of 265-25 in high school with 15 of those losses coming in seventh and eighth grade.

John claims that if he saved every dollar spent on wrestling for his son, he would have enough money to cover tuition at Cornell for four years.

What It Takes To Be Father And Coach:

The struggle John faces as a coach is his continuous battle to prove other athletes and parents that he does not favor his son.

Dr. Gonzalez believes that resentment comes with any sport, and there is always a chance that other athletes may not approve of a father-and-son relationship at practice. This scenario doesn’t change the health of the relationship between father and son, according to Dr. Gonzalez.

John cares deeply about how his players view him and forces himself to hold back when Hunter is competing.

“There were times where I wanted to tell him it’s OK after a tough loss,” John said. “But as a coach, I’m supposed to worry about the entire team.”

John said that he couldn’t enjoy watching his son compete and would have to watch the matches on tape later to view each meet in the perspective as a father. John is excited to see his son compete at Cornell so he can be a father in the stands, but he claims that he won’t be any less vocal as a fan than a coach.

“I’m a nasty fan,” John said. “Much worse than I am as a coach.”

This type of passion has helped John coach every athlete with the same intensity.

President of the Central New York Wrestling Officials Association, Todd Fallon, credits John for keeping his composure when Hunter competes.

“You typically see four out of five coaches get more animated during a match when their kid is competing,” Fallon said. “John’s intensity never changes.”

John’s concern for other athletes has paid off for another three-time state champion that walked the halls of Holland Patent. Alex Herringshaw competed with Hunter for multiple seasons, but never saw him get any special treatment.

Although Herringshaw praises his parents for pushing him into Division I wrestling at Campbell University, he is happy that his father stayed on the sidelines.

“It would be hard if my dad was my coach,” Herringshaw said. “We would butt heads sometimes when it came to wrestling.”

Herringshaw believes that Hunter and his father had a special connection on the wrestling mat that made it easier for the relationship to work.

This connection has led Hunter to an Ivy League school wrestling program with a graduation rate of 98 percent from 2004 to 2009, according to the NCAA’s latest GSR database.

Defying The Odds:

John Richard started his coaching career in 1991 at Webster Schroeder High School but took a job at Mount Markham two years later as a football and wrestling coach. His passion for football in some instances exceeded the love he had for wrestling.

Once Hunter was born in 1999, the Richard family moved to Holland Patent a year later where John was torn on which sport he would solely coach.

“I told him to pick one and be great at that sport,” Gina said.

John viewed the amount of television exposure that football gets as a second-hand coaching method which pushed him toward wrestling.

“Wrestling doesn’t get as much attention as other sports,” John said. “Not a lot of people understand the techniques behind it.”

With the numerous years of experience as a coach and member of a wrestling family, John believed that his son was destined to be involved in the sport.

The pair wrestled on the creamy white rug in the dining room until Hunter could compete in events. John would take his son to practice and Hunter was acclimated to the program from an early age.

According to the Bleacher Report’s NCAA writer, Roger Moore, this type of relationship gave Hunter an advantage because he learned the “in’s and out’s” of the system and the sport.

The push for a wrestling scholarship does not come easy for athletes, though. There are only an average of 9.9 available scholarships per school in the NCAA although Moore claims that many programs have around 30 wrestlers on the roster.

According to the National Federation of State High School Associations and the NCAA, there are 170 high school wrestlers in the country for each available scholarship. With nearly 270,000 high school wrestlers nationwide competing for 1,530 scholarships; the odds are slim to get recruited.

“There are just as many wrestlers in one New York district as there are scholarships available across the country,” Moore said.

Moore also said that schools will also divvy up the 9.9 scholarships in order to give more athletes opportunities. This makes it even harder to get a full scholarship

Hunter has used the support and the athletic genes of both parents to defy the odds, but what is most important to him was the routine his family established at a young age.

This routine helped form a structure in Hunter’s life that Moore believes is vital for every wrestler who wishes to compete at the college level.

“College is a strange land and a stressful transition,” Moore said. “Without structure at home, many athletes will drop out because they can’t function on their own.”

The Transition:

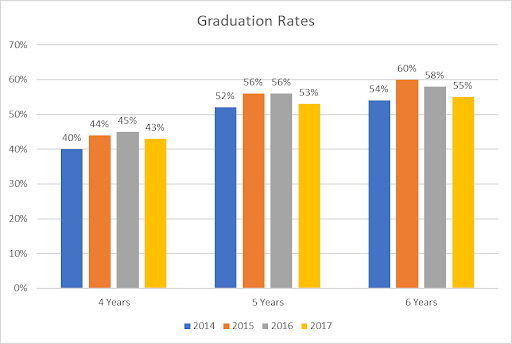

Head Cornell wrestling coach Rob Koll has been coaching the Big Red program for 22 seasons with only three students failing to graduate. This is not the case for all wrestling programs, and in 2016, the wrestling graduation success rate was lower than the Division I average of 80.9 percent.

The graduation success rate,(GSR) is the percentage of students who have graduated from each institution compared to the number that has dropped out. This data includes non-scholarship students and in this case, focuses on Division I athletes.

Out of the 18 men’s sports at the Division I level, the wresting graduation success rate was one of the lowest in 2016 at 76.3 percent. Only FCS football was lower with 74.5 percent.

“Wrestling weeds out the weak,” Moore said.

Moore views parental support as a necessity in order to succeed, but Dr. Gonzalez thinks that parents who are extremely involved with everything their child does can set them up for failure later in life.

Dr. Gonzalez acknowledges two types of parents. The “helicopter” parent keeps their child out of trouble from a distance while a “lawnmower” parent stops all issues in a child’s way to prevent any problems. Dr. Gonzalez thinks that if a parent is too involved with what the child is doing, the kid may eventually struggle to function on their own.

For the Richards, their parenting philosophy has changed over time. Before Hunter’s senior year, John and Gina admit to being a lawnmower parents.

“As teachers, you know what goes on and can happen during high school,” Gina said.

With hopes to get a scholarship, the Richards held Hunter to high expectations in order to prevent any “screw-ups” that could hurt his image.

Although they will continue to show concern as parents, the Richards understand that Hunter needs to learn how to function on his own. This includes having a job, car and extra freedom.

Hunter refers to his dad’s transition to a helicopter parent as him “letting go of the grip.”

This doesn’t mean that John stopped getting involved with his son. He pushed Hunter in the recruiting process which eventually led him to Cornell and coach Koll.

For Koll, John’s involvement to this point is very common among parents and he believes that is how it should be.

“This is the single biggest decision of these kid’s young lives,” Koll said. “You can’t let someone who isn’t even a legal adult make that decision on their own.”

![President Todd Pfannestiel poses with Jeremy Thurston chairperson Board of Trustees [left] and former chairperson Robert Brvenik [right] after accepting the university's institutional charter.](https://uticatangerine.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/unnamed.jpeg)