For the 216,211 homeless women and girls in the United States as of 2018, finding shelter and food is already a daily hardship.

And then, they get their period.

In the United States, 8.3 women experience homelessness per 10,000 people, according to the National Alliance to End Homelessness. Statistically, that is thousands of women who cannot afford basic products and facilities to take care of themselves.

For all of those women, transgender individuals and anyone who menstruates, coping with their menstrual periods while living in the streets, and all that comes with it — cramps, bloating, discomfort or mood swings — is more than a hassle.

It is an added disadvantage and a potential risk to their own lives.

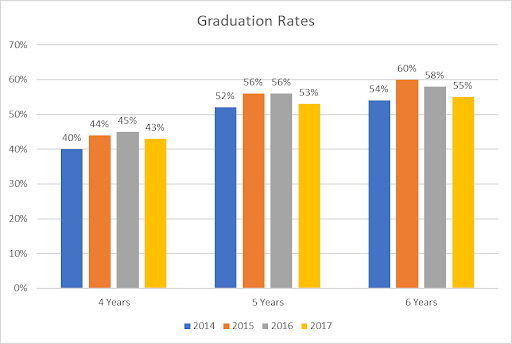

The city of Utica and Oneida County are no different from the rest of the country as homelessness rates grew between 2015 and 2017. A Point-in-Time count of homeless individuals made by the Mohawk Valley Housing and Homeless Coalition reported that in 2015, at least 81 women experienced homelessness in Oneida and Madison counties. In 2019, that number was 89.

While that may be a 9.88% increase, that is still at least 89 women and girls who are struggling month after month.

The face of female homelessness

Yet beyond statistics, there are real stories.

Tracy became homeless at the age of 16 after growing up in the foster care system and running away from one of the House of the Good Shepherds female group homes.

She went from house to house while “praying that nothing would go wrong.”

“With no money and being ashamed with my living situation,” Tracy said. “For sanitary products, I would use toilet tissue which was very uncomfortable and messy.”

As a result of her situation, Tracy ended up developing yeast infections, which cause irritation and discomfort.

“There were days and weeks I would go without brushing my teeth or even showering,” she explained. “I did not want to ask the people that I was living with for too much because they already helped me out by allowing me to stay with them.”

When homeless women decide to resort to alternatives such as tissues, socks, paper towels, plastic bags, towels or clothes, these can lead to several physical and psychological repercussions such as trauma, infections and anemia.

In addition, when a homeless woman does not have enough resources to afford sanitary products, she may wear a tampon for too long in order to save money. That action exposes her to developing what is called as “toxic shock syndrome,” a bacterial infection that can be life-threatening.

Women in reproductive years cannot choose to stop the natural process of getting their periods — unless they take birth control or go through certain medical therapies, which is costly for those who struggle to find shelter and food to begin with. Every month becomes a race against time to purchase femenine products and have access to bathrooms and clean clothes.

Poverty and homelessness: A structural issue in the United States

“This story is not unusual,” said Diane Berry, community activist and member of the Planned Parenthood Council Action. “It happens to a lot of girls.”

Homelessness among younger populations is mainly linked to family dysfunctions, according to Berry. Many children and young people will go homeless if their parents are not able to provide a safe environment, usually as a result of addiction or incarceration. When those situations escalate and there is physical and sexual abuse, children will be placed in foster care but, in many occasions, teenagers will run away, Berry explained.

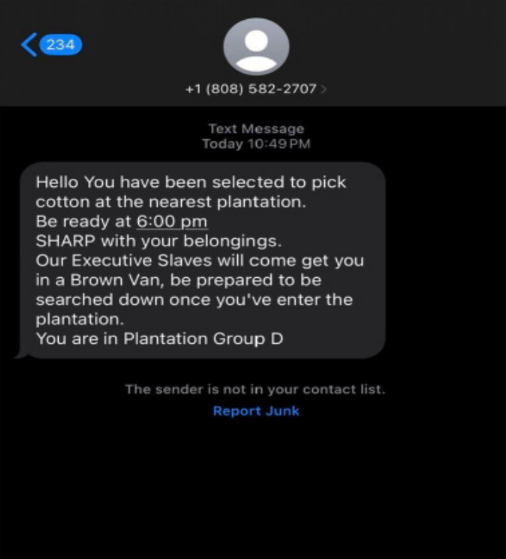

Among African Americans, immigrant families and transgender individuals, the issue is much worse, according to Berry.

“Every burden of poverty is much deeply felt by people of color and transgender people, who are the most murdered and who have the highest rate of suicide,” she said.

Homeless women may be blamed for her lack of effort as the cause for her situation, said Janine Phillips, communications and outreach specialist for the YWCA Mohawk Valley.

There are many situations in which society blames women for their own misery, according to Phillips, such as not finishing high school due to sexual or physical assault, an unwanted pregnancy or lack of resources.

“While people who have resources and healthy life situations may think the woman is making bad choices,” Phillips said. “If she comes from a family who cannot afford basic necessities, there are no other choices to be made unless she knows who to turn to for help.”

And sometimes, those women do not even know where or how to ask for help.

“Society doesn’t see this,” Phillips said. “It only sees a woman who is lazy or looking for a hand out.”

Affording a necessity

At stores such as Walgreens, a box of 36 tampons or pads costs around $6.97 — without tax. When buying food is already a hard enough, those essential items can be too expensive.

To support individuals and households in need, the federal government has put in place initiatives such as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), commonly known as food stamps. This federal aid provides assistance to eligible individuals and families to purchase food items. However, the U.S. Department of Agriculture specifies that hygiene products are not included in the list of products that can be bought using SNAP benefits.

Because food stamps do not cover femenine products “even one single dollar is going to harm people in poverty,” Berry said.

As a result of the unaffordability of femenine products among underserved populations, several social movements have risen nationwide to demand the elimination of the “tampon tax” on the basis that those are considered luxury products and should be tax exempt.

On this line, Peter Gaughan, Administrative Assistant for the Womyn’s Resource Center said that feminine items are very much “a necessary product for a dignified standard of living.” Without them, women are prone to health issues and social exclusion, he explained.

“A period can inhibit your ability to do basic things like go to class, practice, office hours, work, and even studying if you don’t have the appropriate products,” Gaughan said.

Female equals extra vulnerability

Shelters and organizations recognize the struggles that homeless women face, simply because they happen to be female and homeless. From domestic and sexual violence, to pregnancy and post-traumatic stress disorder, those situations place women in situations of high vulnerability and even at risk of death.

Among women, domestic violence is one of the leading causes of homelessness as they are forced to leave their household to escape situations of danger, said Kari Procopio, chief operations officer for YWCA Mohawk Valley.

“When a woman decides to leave an abusive relationship, she often has nowhere to go,” she said. “This is particularly true of women with few resources. Lack of affordable housing and long waiting lists for assisted housing mean that many women and their children are forced to choose between abuse at home and life on the streets.”

The effect of domestic violence goes beyond what can be thought of as a one-time homelessness episode. A 2017 study by the Institute of Labor Economics (IZA) found that those women who had suffered intimate partner violence in the past were more likely to stay in a cycle of intermittent homelessness.

Sometimes, homeless women are not able to find shelter as they are frequently filled to capacity and must turn away “battered” women and their children, Procopio said.

Others, especially younger women, simply do not want to go to shelters where they live in small spaces with other people who are sometimes battling addiction and mental health issues, Berry said. These teenagers often worry about their few belongings being stolen and not being safe.

Factors such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) can also impact those women’s ability to take care of themselves, and therefore, finding a safe place to sleep and managing their finances, according to Procopio. That stress associated with trauma and homelessness often lead to lives of substance addiction, which makes it harder to find stable housing. Some of them eventually experience chronic homelessness when the situation continues even after one year.

Poverty and homelessness also make women more vulnerable to sexual violence, Berry said. One of the coping mechanisms involves finding temporary housing with men in exchange for sex. A practice that is known as “shacking up,” according to the IZA study.

To avoid these situations, women’s shelters teach how to become financially independent to make decisions that benefit them.

“When a woman can make those choices for herself,” Procopio said. “That is the most empowering thing.”

Helping locally

To respond to women escaping domestic and sexual violence, local organizations such as the YWCA Mohawk Valley provides emergency shelter services and hygienic products in their Hall House, a 16-bed facility in Utica and Lucy’s House, a six-bed shelter in Rome. Both are 90-day programs.

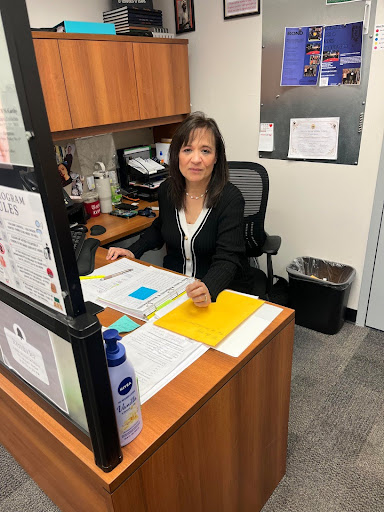

The United Way of the Valley and the Greater Utica area offers several services to women and families at a disadvantage. Services that are essential to create a stronger community, said Betty Joan Beaudry, director of community impact.

Beaudry is also director of the 2-1-1 Mid-York, a phone service that connects community members with resources such as healthcare, substance abuse services, shelter and housing options as well as support groups, among others.

Out of the more than 4,000 service requests that the 2-1-1 Mid York received from people in Oneida county, housing and shelter needs were the second most common reasons why people called, just after employment and income requests. Among housing and shelter requests, 62 percent of them involved temporary housing and rent assistance.

The data by the 2-1-1 service show that even though the Mohawk Valley Housing and Homeless Coalition counted a few hundred homeless women, requests for food, shelter and housing show a much deeper issue of poverty in Oneida County.

At Emmaus House in Kemble Street in Utica, women and children find a safe space away from the streets. The shelter can accommodate up to 15 women of all ages and their children. There, they receive the support to not only address their needs and those of their children but to find permanent housing.

While the Department of Social Services of Oneida County covers their stay, the women also have to show “initiative” to improve their situation, according to the shelter’s executive assistant, Christina Mason. This means that they have to actively seek employment and housing as well as to check in with social services weekly to maintain the voucher that allows them to continue at Emmaus House.

The shelter also provides femenine items, diapers and other toiletries as well as socks and underwear. Women can shower every day, an indispensable task when menstruating.

While organizations have started including feminine products in their care bags, some shelters still do not even provide feminine products as a result of the stigma surrounding menstruation, and because they ignore that it is a necessity, according to Berry.

A volunteer with the Municipal Housing Authority said she went against housing policies and provided cash to a client who was sleeping in the street and had no clean underwear or sanitary napkins because many “blessing bags” did not have feminine products.

“This is a big deal,” she said.

Homeless and female body functions: Two stigmas face to face

The inability to speak openly about a natural process such as the menstrual period is an example of the social stigma that surrounds it, Mason said.

When that shame prevents homeless women from seeking help and resources to deal with their period, the consequences of them resorting to cheaper and less safe alternatives can even become life-threatening as they expose themselves to infections.

That is when two stigmatized situations come face to face.

The stigma surrounding homelessness and poverty has to do with the idea that those individuals are responsible for their own situation, which makes accessing resources and aid “near to impossible,” Gaughan said.

In addition, the stigma that surrounds menstruation belittles women in a way that it is difficult for them to be taken seriously, he said.

“Some women do not have the agency to ask for help,” Berry said. “The individualistic mentality in this country causes homeless women to be embarrassed of their situations and their bodies.”

The negative views on homelessness and female bodily functions, compounded with the trauma of gender-based violence prevents women from seeking help, according to Procopio.

“It is especially difficult when women continue to live in a patriarchal society which perpetuates rape culture and threatens reproductive health and autonomy with legislative action,” Procopio said.

When society tells homeless women that they are the ones to blame for their misery and that their natural bodily functions are dirty and shameful, they face a double challenge: being homeless and female.