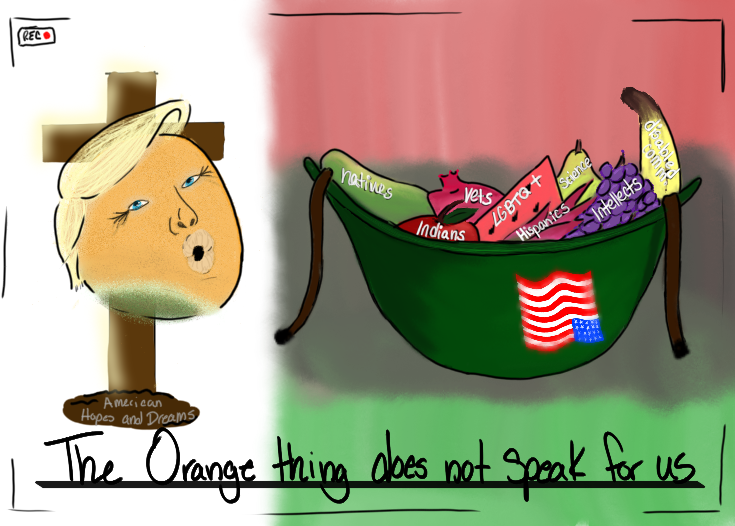

As Americans sit around the table on the last Thursday of November, there is a plate that is missing; where do Native Americans sit at the Thanksgiving table?

For centuries, this fall holiday has proudly marked the first steps of the United States which cannot be understood without the influence of those Indigenous peoples who welcomed the pilgrims and assisted them in a time of need.

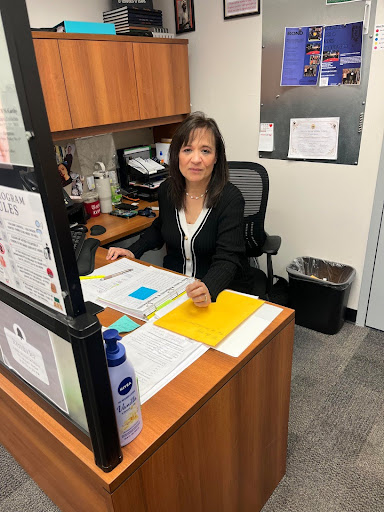

“For many of us, thinking of this time is a story of survival,” said Mary Hayes-Gordon, director of program operations at the Young Scholars office and a member of the Occaneechi Band of the Saponi Nation, a Native American community from North Carolina.

“(Thanksgiving) was really when the Europeans came here,” she said. “It was the beginning of the end of our lives and our culture as we knew them.”

Despite the historical associations of Thanksgiving, Hayes-Gordon said the American holiday is her favorite, as it is a time of reunion with her family.

“It’s a time of connection, establishing new traditions and carrying on with those that have been passed down,” she said. “I am not thankful that the pilgrims came to this continent but I am thankful that I get to spend this time with my family and strengthening our ties.”

For Hayes-Gordon, Thanksgiving is based on the idea of two cultures coming together where one was in distress and the other helped overcome it during a continued period of time, not just once.

“The (Native Americans) gave that support to keep those Europeans alive because they didn’t have the skills or resources to stay alive,” she said. “It is a great idea to celebrate and acknowledge that we should be thankful. Many people look at it from that perspective.”

The general view about indigenous people has drastically changed, nowadays, with a more media-driven narratives of who they are, according to Hayes-Gordon.

The idea of survival lies in the genocide of Native Americans that took place, not only in North America, but in other continents such as Australia, Asia, Africa and South America.

“But some of us are still here and we are 21st Century Americans,” Hayes-Gordon said. “We are not a movie version of the Navajo tribe living in the middle of the desert. We are professors, doctors, pharmacists, brick masons, farmers. We are part of the American culture.”

Hayes-Gordon is originally from North Carolina but grew up in St. Lawrence county, New York, which is near the Canadian border. She pursued her Journalism degree at Utica College and likes the idea of the city of Utica being a home for many immigrants and refugees.

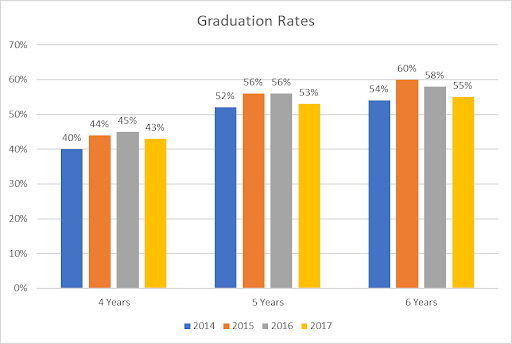

At UC, only 0.449 % of the student population identifies as American Indian or Alaskan Native, although student organizations with Native American representation existed on campus not too long ago.

Giving thanks is embedded in most indigenous cultures, according to Hayes-Gordon. For her, Thanksgiving is almost a “sacred” time.

“Everyone comes to my home and we carry on our traditions,” she said. “We teach them the truth of our people. The truth of our history.”

The celebration of Thanksgiving as a story of two people coming together and working to live together.

“If the (U.S.) had continued in that vein, it would be a totally different world,” she said. “If you look at the story from the lens of cultures connecting and helping each other survive, then it’s a great way to view and live in this world.”

Assistant Vice President of Student Affairs and Dean of Students Timothy Ecklund shared a similar perspective about the true meaning of Thanksgiving.

“One would think that there would be a great deal of pushback about Thanksgiving among the Native American community,” Ecklund said. “But there is not a lot of finger-pointing and resentment because those would not be seen as good traits within that culture.”

For Ecklund, whose doctorate area of research focused on the experiences of Native American college students, it is important to help native people sustain their culture “because they are on the brink of extinction with each and every decision that is made about their community.”

Given the “tragic” history associated with Native Americans, Ecklund said there is much more to be celebrated on Thanksgiving such as the community way of thinking about the world.

“When the first contact occurred with the native peoples, they did the only thing that their worldview would allow them to do: They welcomed them,” he said. “Their culture is to help others and help them to survive.”

Ecklund thinks Thanksgiving should be used to not just “romanticize” past relationships with Native Americans but to understand our relationship today.