Students and faculty express concern over costumes depicting minorities

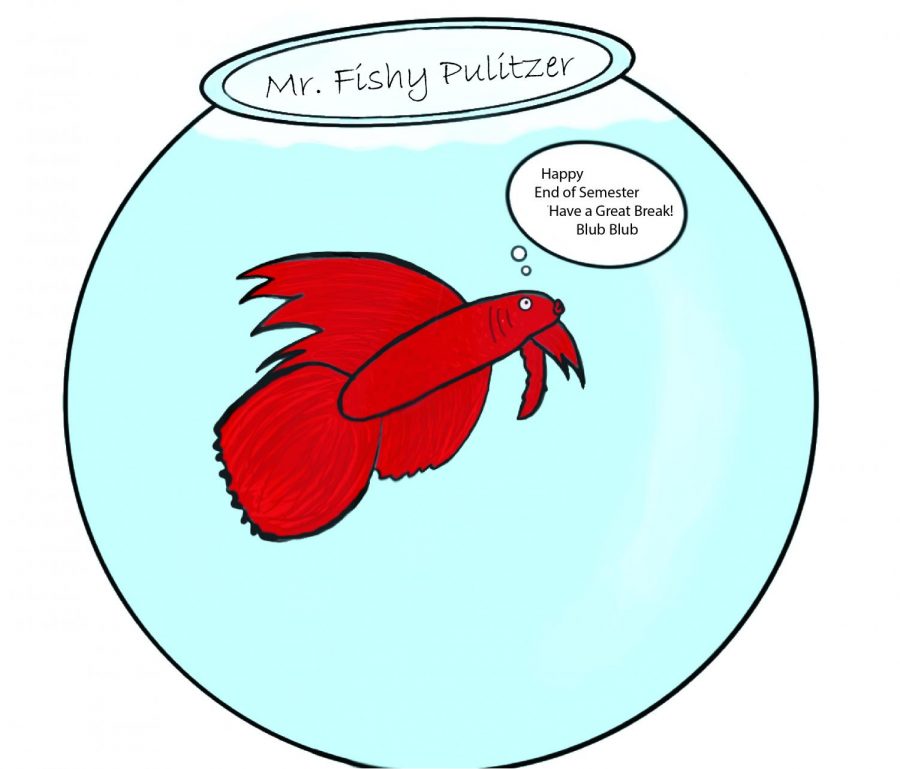

Halloween is a time when people get creative and dress up in many imaginative ways. From Native Americans wearing buckskin, to Mexican people in moustaches and wide ‘sombreros,’ as well as Arabian sheiks and blackface.

In the beginning of October, the Black Student Union held an event in Strebel to inform students about the dichotomy of cultural appreciation versus appropriation, especially during Halloween. That was the only opportunity for students to gain knowledge about the issue. The Dean of Diversity Alane Varga sent out an email on Wednesday night reminding students to ensure that costumes are “respectful of all cultural and gender identities.”

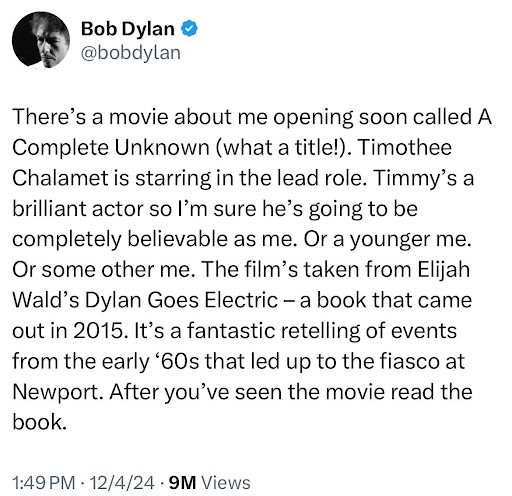

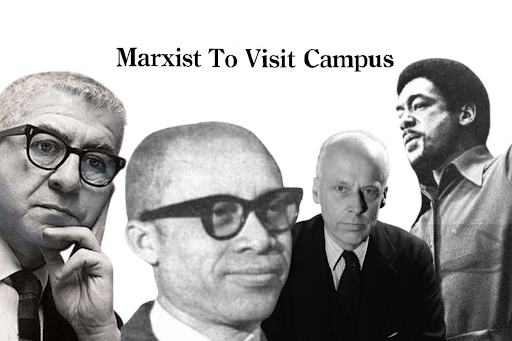

Even though those representations of other cultures take place during a holiday and are designed for entertainment purposes, images such as blackface are rooted in a “very racist history,” Professor of History Clemmie Harris said.

Such history dates back to the 19th century when theatrical representations of black people as depicted by whites became a common form of entertainment, giving rise to America’s first pop culture, Harris said.

From slavery and oppression as a result of the Jim Crow laws, to family separation and traumatic arrests at the Southern border, representations of minority groups in America have very specific histories of human suffering, Harris said.

“That suffering is not resolved now and it is going on to this very day,” he said. “If you have someone who engages in that and is ignorant of that history, it says an awful lot about the role of history to inform our nation and the world today.”

The continuity of those representations of minorities means that the political, cultural and economic foundations of old racist images still have power, according to the History professor.

Such power could be seen in recent months, with clothing lines such as Prada, Gucci and Burberry that were involved in scandals after releasing items that depicted blackface and a noose. Politicians such as Virginia Governor Ralph Northam and recently re-elected Prime Minister of Canada Justin Trudeau also experienced backlash after old photos of them in blackface came to light this year.

“The real key here is the recognition that […] there was a type of privilege that they experienced,” Harris said.

Such privilege leads people, especially white people, to take part in what is called cultural appropriation, according to Harris.

“At the end of the day, when you have people who decide they are going to dress up for Halloween as a costume that is reflective of a historically marginalized group,” Harris said. “Then the question becomes, what is the larger intent behind?”

Students at UC expressed their rejection of racist costumes and said that it is a behavior in which they have witnessed their peers engaging in.

Senior Gabriella Felipe said she has seen other UC students dressed up as “Mexicans wearing hats and moustaches” during parties such as the Beer Olympics.

She defined cultural appropriation as taking an aspect of a culture, “an ingrained part of who they are” and benefiting off of it, while ignoring the social issues and histories associated with that group.

“(Cultural appropriation) is upsetting because you don’t see these issues if you are not the one that is affected by it,” Felipe said.

Having conversations that tackle issues of cultural appropriation would be beneficial for everyone in the community, according to Felipe.

“Discussions like this would prevent white people from going into the world oblivious and ignorant to the issues that people of color around them face,” Felipe said. “It’s also important for students of color so that they recognize a lot of things that are wrong and to learn what is offensive and what is not.

Sophomore Manelyn Sysamouth, president of the Asian Student Union, said she sees people dressing up as other cultures for Halloween as a “misunderstanding” or a lack of interest for historically marginalized groups.

“It is inappropriate to suddenly think that it is cool to wear something from other cultures when, for the longest time, those from that culture were either frowned upon or judged for what they wore,” Sysamouth said.

She referred to seeing people dressing up as other cultures as a “slap” in the face.

As opposed to appropriation, which takes elements from a culture for a personal gain, Sysamouth defined cultural appreciation as the act of honoring and being respectful towards another culture to gain knowledge.

“People need to understand that cultural wear is more than a costume, a fashion accessory and more than expressing yourself,” she said. “When you are wearing cultural costumes, they could have values and a history that is unknown. Do your research before you go out in the clothing you wear and want to take a nice picture for Instagram.”

Senior Cindy Borgen said she found cultural appropriation in the form of Halloween costumes “very offensive and disrespectful,” and added that she sees this behavior every year.

Borgen is a member of Fuerza Latina and a sister of the Latina-oriented sorority Omega Phi Beta.

She mentioned the importance of making, especially white people, understand the history and values behind different cultures, which is reason enough why they are not to be used as a costume, she said.

“It is fascinating how so many people discriminate against minorities, want them out of American soil and have so many negative ideas and stereotypes about them,” Borgen said. “Yet they feel it is okay to dress up in ways to represent those cultures.”

As a Latina woman, Borgen said she feels uncomfortable to see costumes that depict Latin American culture “because I know the struggles that a Latina(o) faces on a daily basis.”

Like Manelyn Sysamouth, Borgen described that type of appropriation as a slap in the face and mocking their identities and their values.

For Borgen, seeing white people dressing up as other cultures conveyed a message of privilege, adding that “they can get away with things like that and feel that they are superior,” she said.

“It definitely sends a message of ‘I’m above you,’” Borgen added. “Just because you have “minority” friends does not make it okay. Ask questions if you are not 100 percent sure.”

When addressing the topic of individual expression that involves using racist imagery, Harris said it is not only an individual issue, but an institutional one that affects the college in general.

“If people at UC do not know that those images are offensive, it says something about that person but it says more about the culture here at UC,” he said. “I would also argue that the institution is failing to put forward a curriculum that helps to have discussions about these particular ideas.”

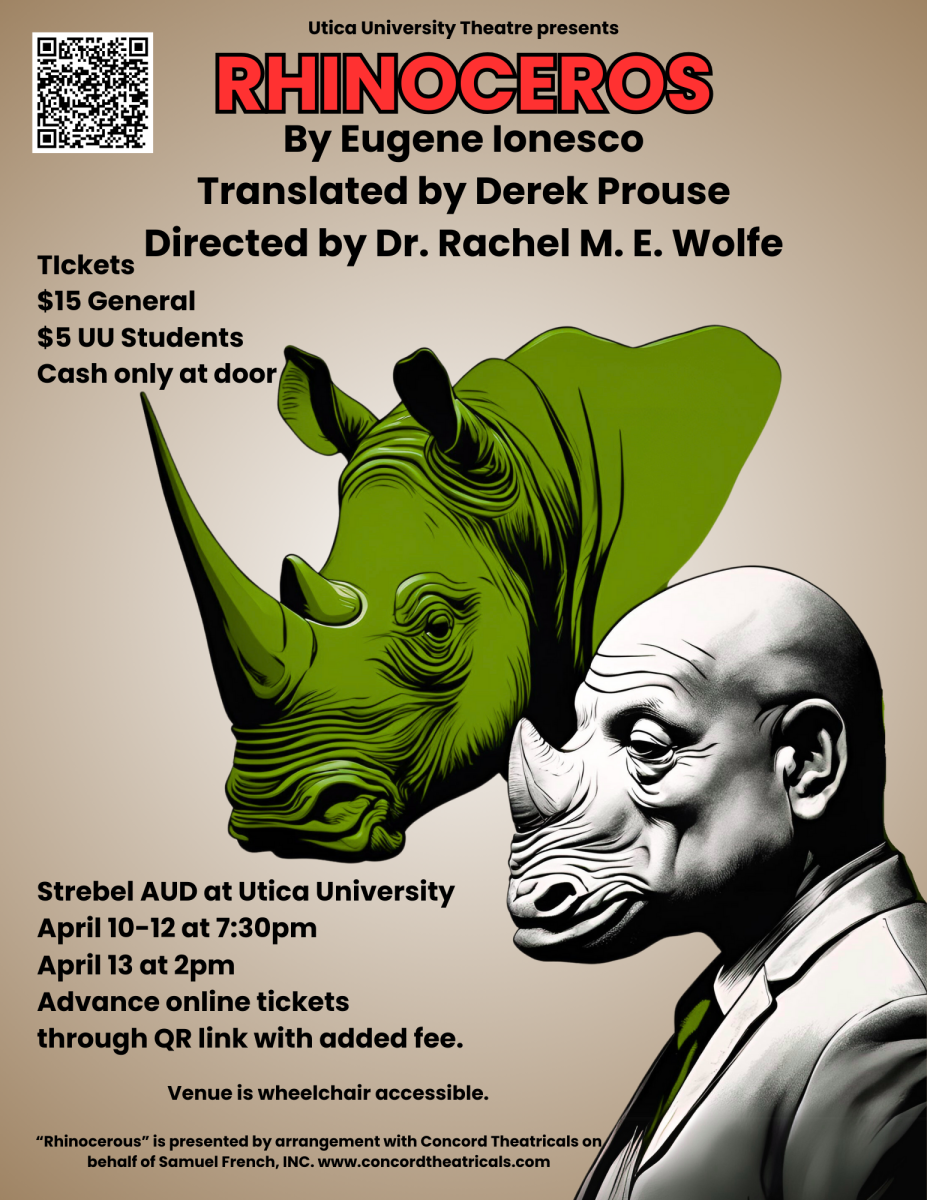

Harris also mentioned last Spring’s incident, when the photo of a white UC student wearing a noose around his neck in Strebel Lounge spread on social media.

“People have a right to basically confront anyone wearing those particular images, and say to them in a respectful and articulate manner that it is not acceptable,” he said. “Transformation […] is going to require an enlightened community at UC to decide what are acceptable and unacceptable forms of expression because, only when one is enlightened, then they have the power and the lessons of history on their side.”