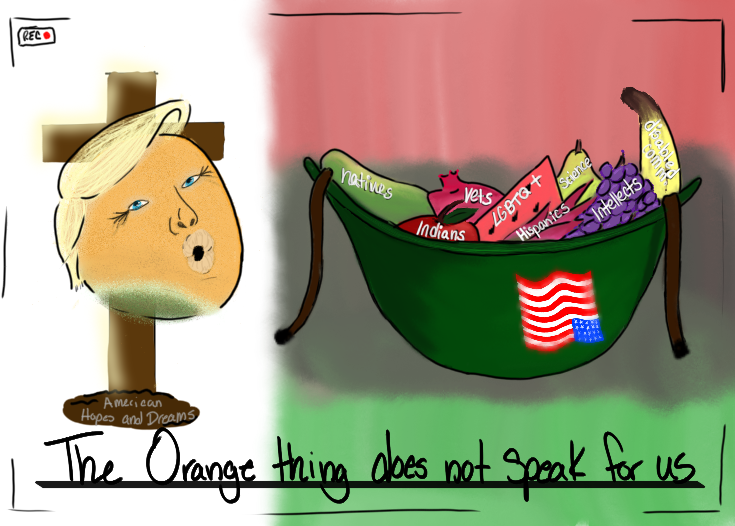

Mired in controversy, Democratic Gov. Ralph Northam remains in office three weeks since a page from his medical school yearbook containing a picture of two people — one dressed in blackface and another in a Ku Klux Klan costume — was brought to light.

Northam has since denied that either person in the photo was him but admitted that he painted his face black to portray pop singer Michael Jackson for a dance contest during the 1980s. Despite backlash and calls for his resignation, Northam has maintained that he will not step down from office and will dedicate the three remaining years of his term to racial equity within his state.

While Northam’s political future ultimately rests in the hands of his state’s legislative body, this event has pushed the far-reaching presence of blackface throughout American history into the public eye.

And this history is one that is almost as old as America itself.

Blackface as a means of performance art, known as minstrelsy, began in the early 1830s when performers in New York City began covering their faces with burnt cork or shoe polish to mimic enslaved Africans.

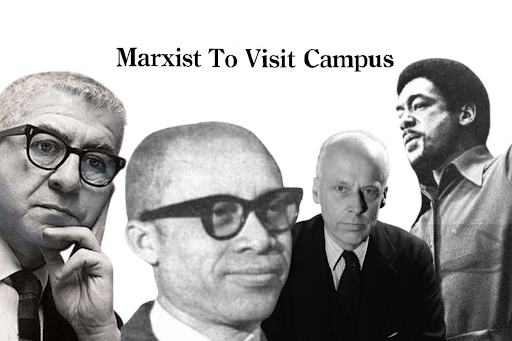

But blackface soon became a means to “push capitalism, reinforce white supremacy and ultimately [undermine efforts to reform race relations],” explained Clemmie Harris, a Utica College professor of American History whose focus includes Africana Studies.

By the mid-1840s, minstrelsy had created set stereotypes and an “entertainment subindustry” of sheet music, makeup and costumes, according to the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture. Minstrelsy expanded into the South in the ensuing decades, as performers like Thomas Dartmouth Rice popularized fictional characters like Jim Crow — the name that would be used to identify segregationist laws in the American South from the end of Reconstruction until the beginning of the civil rights movement in the 1950s.

At the beginning of the 20th Century, blackface was popularized by the development of new forms of media technology, such as the motion picture. Films featuring blackface, most notably D.W. Griffith’s “Birth of a Nation” in 1915, were widely distributed and well-received by the public.

President Woodrow Wilson’s White House screening of “Birth of a Nation,” which is a propagandized retelling of the Reconstruction era, only served to legitimize the presence of blackface in American pop culture, Harris explained.

“The connection between the way in which blackface as an art form becomes a commodity is to understand that capitalism is the key to the early period and the regeneration of blackface today,” he said. “In other words, a market for those particular products is what shapes the supply for those particular products.”

And that same market still exists, Harris said. Examples of the manifestation of this demand include recent controversial clothing, shoes and accessories made by luxury fashion brands Gucci and Prada and singer Katy Perry. These products were quickly discontinued after a recent public outcry over their resemblance to stereotypes traditionally associated with blackface performers.

Even today, evidence suggests that Americans do not uniformly see blackface as a “bad thing.” A recent YouGov poll found that just 58 percent of Americans were opposed to blackface, while 42 percent either did not see it as a problem or were undecided.

“That type of artistic expression is also interpreted as free speech,” Harris explained. “And even though that is speech that denigrates black people, in many circles, one would argue that that is protected speech in the same way one could argue, ‘Yes, the N-word is wrong, but it is protected speech.’”

Considering blackface’s history and lingering place in American society, Harris was not surprised by the revelations over Northam’s past.

“What do we see [in the yearbook photo]?” Harris said. “You have the same type of framing as that of ‘Birth of a Nation’ — it’s ‘Birth of a Nation’ all over again.”

Harris sees Northam’s intention to work on racial reform as “trade” with constituents more so than a method of reconciling with his past.

“The trade is that the pressure from those most affected by the history of blackface, his African-American constituency, will win his trust with the promise that he will deliver on particular policy prescriptions to deal with issues of racial inequality,” Harris said. “It’s the only political negotiation that he could ultimately pursue at this particular moment.”

Regardless of Northam’s political future and the current national conversation involving blackface, Harris ultimately sees “wholesale” reform involving race as unattainable because the talking points around both these issues “do not really go deep enough.”

“This (the conversation around Virginia) is a moment,” he said. “There may be some good things that come out of it, but America will move past it because America does what America always does, which is only address issues of race when there’s a focusing event followed by a return to the normal once that focusing event has taken place.”