It’s around noon in the basement of Hubbard Hall at Utica University. The space is quiet but purposeful. A few students step in, each greeted warmly, and leave with a more full backpack—some are stocked with pasta, granola bars, maybe even toiletries. No one says much, but their expressions say enough: relief, gratitude, maybe even lingering shame.

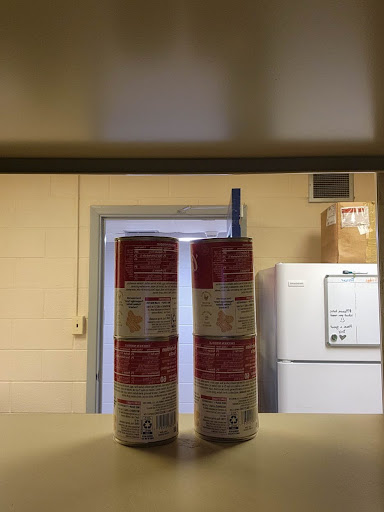

This is the Tangerine Grove, the university’s modest but mighty food pantry. And for over a thousand visitors this academic year alone, it has been a lifeline.

Food insecurity among college students isn’t always visible—but it’s real. At Utica University, a growing number of students are relying on resources like the Tangerine Grove to get by. While many on campus remain unaware—or too embarrassed to ask for help—staff and student leaders are working behind the scenes to ensure no student is left hungry.

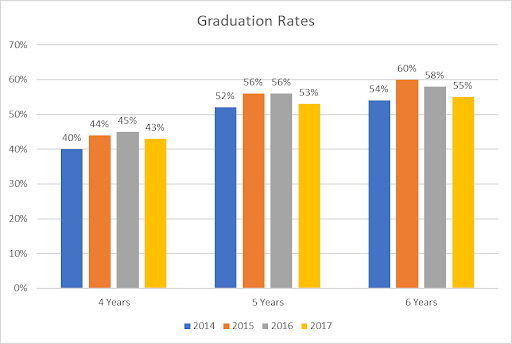

Nationally, nearly 38% of college students experience food insecurity, according to a 2023 report by Temple University’s Hope Center. These students are often forced to choose between essentials like rent, textbooks and food. And they’re 22% more likely to drop out or delay graduation, according to the Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior.

What’s more, many of these students do not qualify for government assistance programs like SNAP, or they face bureaucratic hurdles when applying. Even when they do qualify, benefits may not be sufficient or sustainable. The problem is systemic—rooted not only in individual circumstances but in gaps within broader educational and social policies.

The Food Bank of Central New York reported serving 178,000 people across central and northern New York back in 2017, a statistic that included services in Oneida County. However, more recent data—especially relating specifically to college students—is hard to come by. But those on the front lines of the issue in Utica say students are very much among the hidden hungry. In 2024, the Food Bank reported that it supplied enough food in its 11-county service area to provide 18.5 million meals. College students would be included in that statistic.

“As the previous vice president for our Student Government Association (SGA) and the incoming chief justice, I’ve seen firsthand how urgent this issue is,” Utica University student Xavier Moore said. “During my first semester, I learned about the Tangerine Grove, and the need for it hasn’t gone away—in fact, it’s grown.”

Moore said the pantry’s original donor base has dwindled, and it now relies heavily on sporadic donations and community drives.

“We’ve done food drives, like the recent one by Brothers on a New Direction (BOND) that challenged departments to donate, but we all know that’s not enough. This is a crisis.”

That crisis is becoming more acute. The Tangerine Grove is currently in danger of losing a critical grant that has helped sustain its operations. Without that funding, its future is uncertain.

For Moore and others in SGA, food insecurity has become one of the most pressing issues discussed across cabinet meetings and student forums. “We’ve had students say they can’t focus in class because they haven’t eaten,” he said. “That’s not just a health issue—that’s an academic equity issue.”

Evelyn Enriquez, the incoming SGA president, echoed those concerns—and added personal insight because he is familiar with food insecurity.

“Unfortunately, I’ve lived through it all my life and still face it on campus,” Enriquez said. “Between tuition, housing, and food, it’s hard to keep up—and the cafeteria options are often poor. Many students are skipping meals.”

She said the issue worsened after recent changes to Utica’s dining hours.

“Some students who relied on late-night food options were just left without alternatives. For those already stretched thin, it made things worse,” she said.

Several students informally described their situations on the condition of anonymity. One student said they often stretch a single box of mac and cheese over three days. Another shared that they once chose to go to class hungry rather than miss attendance and lose participation points.

“There’s only so long you can function without food,” the student said. “But sometimes, you have no choice.”

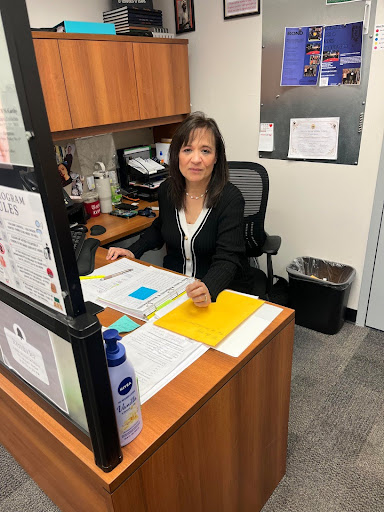

Erin Kelly, program director of Dietetics and Nutrition at Utica University and the lead coordinator of the Tangerine Grove, said the pantry was born from student needs.

“We opened in January 2020 after a lot of planning and research,” Kelly said. “But then the pandemic hit, and we had to shut down. It didn’t reopen until November 2021—this time in the basement of Hubbard Hall.”

Since then, it’s quietly served hundreds—even as it struggles to stay afloat.

In 2024 alone, the Grove logged 1,270 visits from 140 unique clients.

“Most people come around lunchtime,” Kelly said. “About 77% of our users don’t have personal transportation. That’s the only clear pattern we’ve seen.”

Lack of reliable transportation further limits students’ access to off-campus resources like grocery stores or food banks.

“It’s not just about having no money,” Kelly said. “Sometimes it’s about not being able to get anywhere to use the money you do have.”

Kelly juggles everything from volunteer scheduling to grant applications. A recent fundraiser by a local bar helped immensely, but consistent funding is a challenge. “If we lost our funding entirely, it would be catastrophic,” she said. “Food prices are only going up.”

Moore said she believes student advocacy is essential. “We’ve tried to lead by example, pushing departments and student orgs to contribute. But ultimately, the pantry needs long-term support,” Moore said. “Before summer, we’re expecting the pantry’s reservoir to be dry.”

Enriquez sees awareness as a critical hurdle.

“Many students don’t even know where the pantry is or think they shouldn’t use it because someone else needs it more,” she said. “But that’s not how it works. Right now, it’s empty—not even snacks left.”

To that end, she’s planning to launch a campus-wide education campaign about food insecurity. “We want to demystify it,” Enriquez said. “If we don’t talk about it, we can’t solve it.”

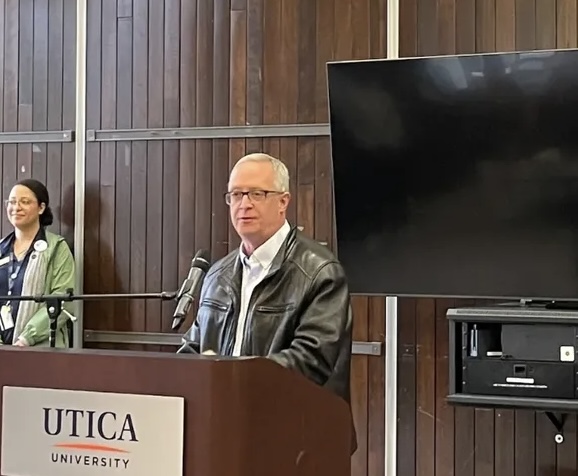

The stigma around food insecurity remains powerful. “It’s hard to tell who’s struggling,” Dean of Students Richard Racioppa said. “Students don’t talk about it. It’s embarrassing. And asking for help is tough.”

Racioppa said while some resources—like the Pioneer Persistence Fund—exist for short-term help, they’re not designed for the ongoing nature of food insecurity.

“We try to direct students where we can,” he said, “but we know this is a deeper problem that’s going to require structural change.”

“We have the vessels for communication—bulletin boards, TV screens—but that doesn’t mean we’re reaching the right people in the right way,” he said. “We need to normalize this issue. Normalize asking for help.”

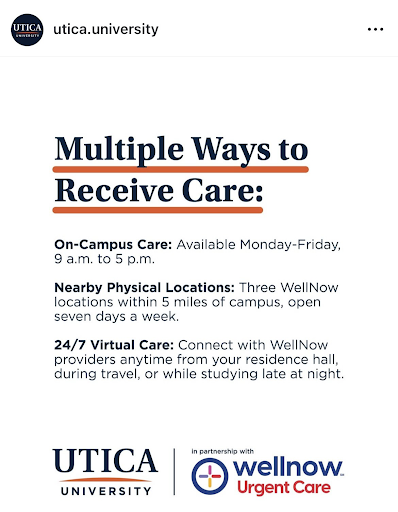

Ariel Rios, executive director of the Student Health and Wellness Center, said faculty and staff can play a larger role.

“We have posters and handouts, but what really works is word-of-mouth,” Rios said. “Faculty talking to students. Staff bringing it up in conversation.”

She also envisions deeper partnerships—with both campus entities and outside agencies. “We’re not currently partnered with food banks or grocery outlets. But we should be. Imagine if we had a recurring partnership with Bargain Grocery or the Food Bank of Central New York.”

Rios suggested further ideas: linking the pantry more closely with residence halls, holding cooking classes and incorporating food insecurity into orientation.

“It’s not just a pantry—it can be a hub of student engagement,” Rios said.

Moore and Enriquez both want to formalize the pantry’s role in university life. “For Fall 2025, we’re pushing for a concrete plan that guarantees the pantry’s longevity,” Moore said. “That might include dedicated budget lines or formal support from the administration.”

Enriquez hopes to work directly with President Todd Pfannestiel to make food insecurity a campus-wide priority. “We can’t just talk about it anymore. We have to act. And Student Government will be doing everything we can.”

She added that new student orientation programs could include a food access tour. “Let’s show students where the pantry is from day one,” Enriquez said. “Let’s make it normal.”

The issue of food insecurity at Utica University isn’t just about filling a pantry—it’s about building a culture of care, awareness and equity, according to the Student Government leaders, and as students continue to lead the charge, the hope is that one day, no student will ever have to worry about their next meal.

Because as Kelly said, “Hunger has no face.”