Utica professors demystify Critical Race Theory at panel discussion

March 9, 2023

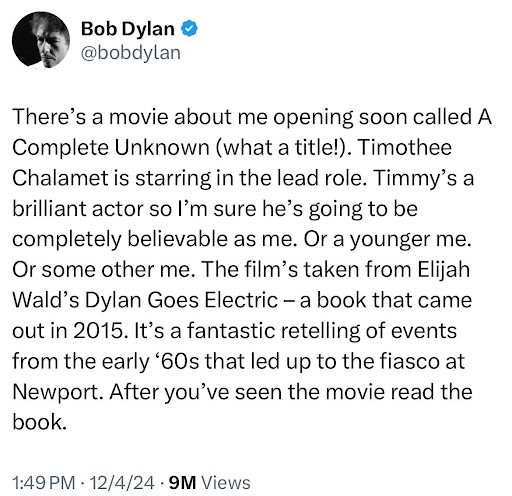

A professor-led panel addressing the media focus surrounding critical race theory was held on Feb.10. The professors explained the history of CRT and provided a clear definition of what the concept means and how it ties to the current political divide.

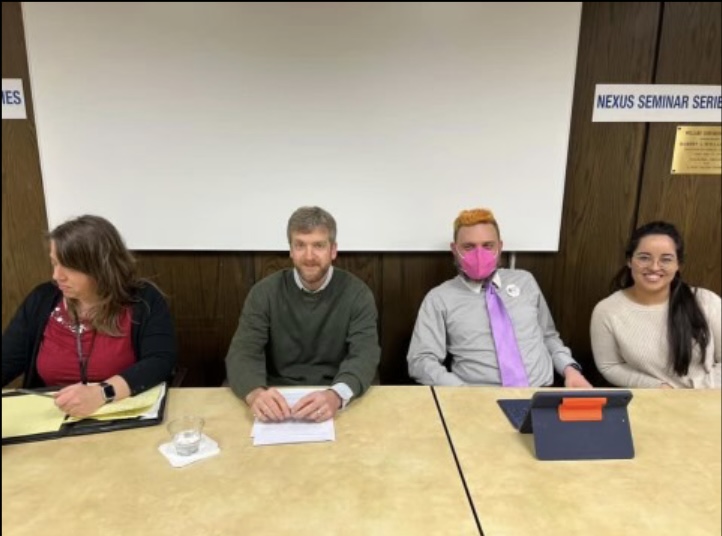

Professors Laurah Klepinger, Daniel Tagliarina, Ane Costa and Daniel Cozart led the discussion and more than 10 faculty members and students attended.

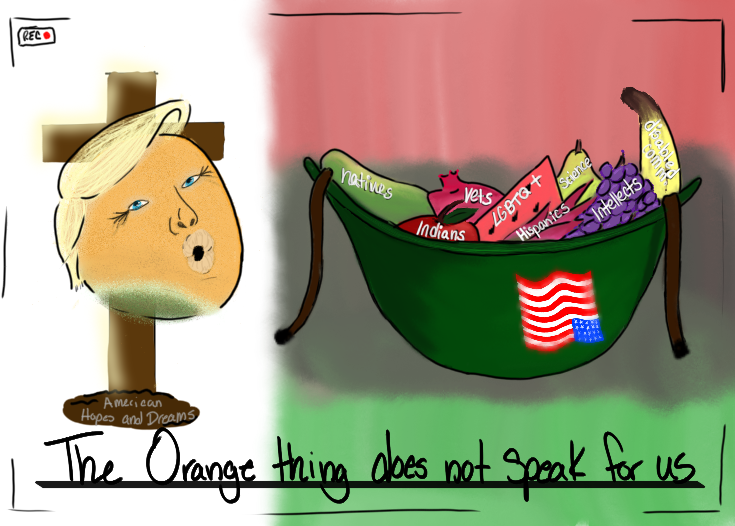

Nine states have recently passed anti-woke legislation banning CRT in schools and most notably Florida Gov. Ron Desantis has led the crusade. DeSantis introduced Stop W.O.K.E. Act legislation to block CRT in schools and corporations.

Tagliarina, associate professor of Political Science, said understanding CRT helps people understand contemporary political events.

“Given the ‘controversy’ over a faux version of CRT, it is important for people to know that the thing they are getting mad about is not CRT, but rather an intentionally misleading version meant to stoke anger for political gain,” Tagliarina said. “This second reason means people are being used by bad faith actors, and knowing about what CRT can let people know they are being misled for the gain of others.”

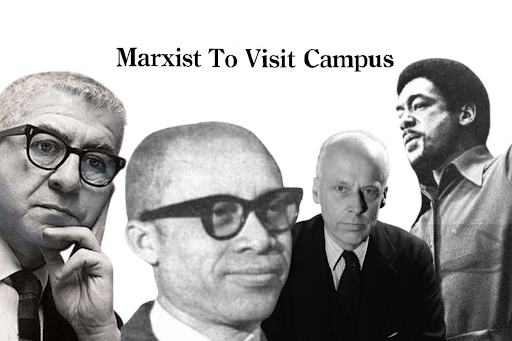

The panel explained how lawyer and civil rights activist Derrick Bell was a pioneer in developing the CRT as a concept. As the former NAACP and Legal Defense Fund attorney, Bell’s contributions to CRT was based on the factual premise that race is not objective, inherent or fixed; the meaning of race is not tangible but just a social construct created by humans.

The social construct of race has led to the creation of systems that favor certain groups of people leaving some to be discriminated against. American laws still fail to consider historical events or policies such as slavery, Jim Crow laws, segregation and redlining that caused power imbalances, which society experiences today. The imbalance of power is reflected in laws, leading Bell to believe that the U.S. justice system was broken and inherently racist.

Bell began his journey as an attorney fighting to desegregate schools in the south and received backlash for this pessimistic perspective from white and black scholars. He viewed many civil rights victories as moral awakenings among whites opposed to progress.

According to Bell, what most viewed as victories against racism, were a result of “interest convergence” and Cold War pragmatism. Bell argued this because, after the desegregation of public schools in the south, whites began the creation of private schools. Black students still attended institutions that were effectively separate and unequally funded, which canceled any real progress in place of the colorblind racism practices that took place instead.

Harvard Law hired Bell as a professor for his teachings of the CRT concept. Leading him to teach; “Race, Racism and American Law,” at Havard and New York University. Bell aimed to use CRT to expose the contradictions of antidiscrimination law and the complexities of legal advocacy for social justice.

Tagliarina explained CRT as “thinking about the law as it pertains to race to help us understand society. CRT does not say white people are the problem.”

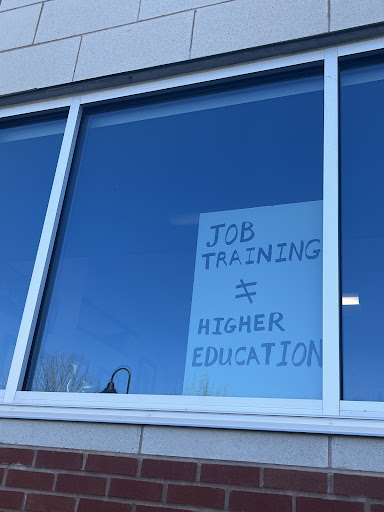

Often critics attack higher education and topics of intersectionality that relate to critical race theory, claiming it indoctrinates children into “Black supremacist ideology.”

Klepinger, an assistant professor of anthropology, raised the question: “Is asking our students to think critically about race or privilege a bad thing? We are called on to be better. It is very important to talk about these terms on a college campus. We, as critical theorists, are creating a more equitable society.”

Confusion around the definition of CRT began with Fox News coverage of the nuance topic increasingly in 2021.

Chris Ruffo, known as the father of anti-woke rhetoric, made appearances on conservative news outlets. Ruffo creates his own false definition that paints adopting CRT in schools as reverse racism against white students. Many have adopted the biased version of CRT introduced by Ruffo, with no mentions of Bell’s original definition of the concept.

Ruffo tweeted on March 15, 2021 “we have successfully frozen their brand—”critical race theory”—into the public conversation and are steadily driving up negative perceptions. We will eventually turn it toxic, as we put all of the various cultural insanities under that brand category.”

Ruffo’s rebrand on CRT has led to divisions in school boards across the country, especially Florida, which has recently banned the teaching of AP African American history in high schools. Legislators see the course curriculum as “inexplicably contrary to Florida law and significantly lacks educational value.”

Forms of color-blind racism exist all around the world, said Cozart, professor of Afro-Latin American History. This issue of colorblind racism does not only exist in the United States as other nations have adopted silent racism practices justifying their actions by comparing themselves to the United States.

Cozart provided an example from South America practices of colorblind racism but in a form of racial democracy.

“Brazil constructed a myth of racial democracy, a practice that encouraged race mixing that resulted in mixed ancestry,” Cozart said. “Leading them to think there was no racism, when in fact there still was, just not written in law like the United States.”

Instead of racism being enacted through policy in those societies, racism was practiced culturally. Blacks were instead discriminated culturally in societies by only being given certain low income job opportunities and preventing social mobility. Blacks were being treated differently as they were not being recognized for their contribution to developing the country of Brazil as we know it today.

When asked about which age is best to introduce CRT, Cozart said the topic is complex and should only be focused on in higher education.

Tanglariana, on the other hand, said “children are never too young to learn and understand race relations.”

The professors encouraged parents to challenge their children to think more critically regarding race as they grow up. Ignoring difficult conversations by banning CRT in the school curriculums is viewed as a step backward to social justice.

Clemmie Harris, professor of African American studies, briefly spoke after the presentation on the power of silent racism occurring in places like Florida. Harris said people must be steadfast in maintaining their convictions.

“You can’t choose your color, but you can choose your commitments,” Harris said. “You can’t choose your parents, but you can choose your politics.”

Sophomore Dakota Alexander said it was interesting to hear the perspectives of each presenter and all the possible ways CRT affects different kinds of people.

“After hearing the presentation, it seemed like the biggest issues were ending the stigma of fear surrounding the subject and facing the complexities,” Alexander said. “It seemed totally possible to not fully grasp the entire concept and still enact change even if through small means.”