The face of an institution: How Utica University’s athletic mascots have evolved

Utica University Marketing and Communication Department

Trax taking the Campus Safety Cart for a joy ride in front of the Utica College sign.

November 3, 2022

The long history behind Utica University’s mascot is a story that only some in the campus community are familiar with. Since the birth of the university, the process of choosing the right mascot to represent the school was a task that had its ups and downs.

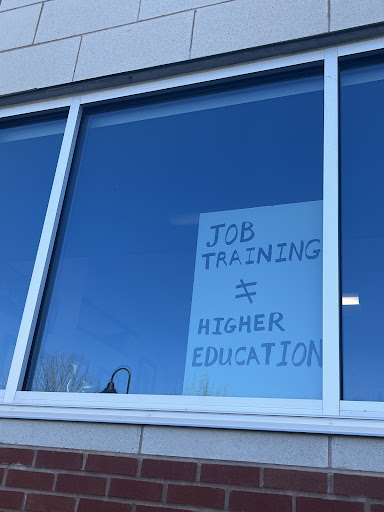

At one time Utica University was known as Utica College of Syracuse University, with Syracuse University hovering over the institution. Utica’s desire to create its own path and come into its own became significantly important.

Paul Lehmann, the Director of Campus Activities from 2000 to 2012, was responsible for coordinating all the events on campus. He also played a key role in the mascot development at Utica College and said one of the things Utica struggled with early on was searching for its identity and how to define itself in relation to Syracuse.

“Syracuse was a behemoth and it can just totally overshadow who you are,” Lehmann said. “There were some parts of it, especially in the beginning that were important to the Utica College students. They would pride themselves that they had a Syracuse University diploma because it was recognized and people know what that was. So how do you maintain that and at the same time create this identity of who you are as your own campus.”

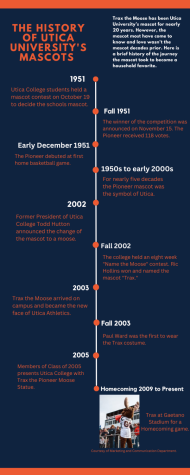

The first mascot

A 1951 Tangerine article titled “Pioneer Spirit Stems From UC’s Early Days” explained a mascot contest held by Utica College students. The contest lasted one month and throughout the duration of the contest, one winner was chosen each week. There were three mascot ideas that reached the final round, including “Monkey,” “Tangerine Braves” and “The Pioneer.”

Madeline Zogby, a first-year student, was the winner during the first week of the competition. Her reasoning for the Tangerine Brave stemmed from Syracuse University’s mascot at the time, the “Saltine Warrior.” Utica University was then the recently created Utica College under the umbrella of Syracuse University. Zogby also added that a young Indian should be pictured on pennants decals.

Frank Chambrone, also a first-year student, was the winner of the contest in the second week for the “Monkey” submission. In the same article, Chambrone was asked about the thought behind the submission.

“I think a monkey should be UC’s mascot because it is humorous and has comical gestures,” he said. “In all school activities and sports, he could bring many laughs from his audience.”

Paul Brown, a junior, won in the third and final week of the contest with the “The Pioneer” submission. After the contest, it was then time to select the final winner.

The students were then tasked to come up with a final decision a week later. The decision was announced at the Student Senate Thanksgiving Assembly in November 1951. The winner of the competition received a $25 savings bond at the first home basketball game of the regular season.

Brown won the mascot contest with 118 votes and said the Pioneer was worthy of being the school’s mascot because it is known for courage and self-resilience.

“The spirit of the colonial frontier is exhibited by Utica College in its founding years,” he said. “Utica College is the pioneer college in the Utica area.”

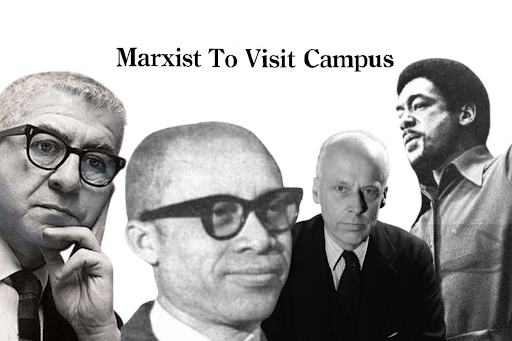

Native American imagery as mascots

The emergence of Native American mascots in the United States started between the 1930s and 1950s. Until the early 2000s, the representation of Native Americans as mascots became a more common theme among collegiate schools. Stanford University’s “Indian” and St. John University’s “Redmen” were two of the many institutions that exploited Native American imagery to insert the “warrior” or “bravery ” mentality in their athletic programs.

In 2005, the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) reached the Native American Mascot decision ruling that NCAA colleges and universities are prohibited from displaying hostile and abusive racial, ethnic, or national origin mascots, nicknames, or imagery at any of the 88 NCAA championships.

According to Executive Committee Chair Walter Harrison, colleges and universities may adopt any mascot they wish since that is an institutional matter. However, as a national association the NCAA believes that mascots, nicknames or images deemed hostile or abusive in terms of race, ethnicity or national origin should not be visible at championship events that the association controls.

Utica’s former Pioneer mascot was a Daniel Boone-like figure consisting of a white man in a raccoon skin hat who carried a rifle. Not only did it showcase racial insensitivity and hostility, the mascot also highlighted the ethnocentrism that portrayed Native American stereotypes. This kind of imagery concerned the NCAA Minority Opportunities and Interest Committee (MOIC). These concerns grew and sparked the coming of this decision as MOIC’s mission is to advocate the causes of ethnic minorities by fostering an inclusive environment that creates a culture that promotes fairness and equitable access to opportunities and resources.

The NCAA objects to institutions using racial, ethnic and national origin references in their intercollegiate athletics programs because they don’t represent the values of the NCAA constitution. The NCAA promotes cultural diversity and ethical sportsmanship as non-discrimination acts. At the time of the decision, 33 schools were asked to submit evaluations to the NCAA. Of those 33 schools 14 removed all references of Native American culture or were told not to have Native American culture as part of any of their athletic programs.

Evolution during the 1950s to early 2000s

Even though the Pioneer mascot was active before the ruling in 2005, Utica College began launching its independence from Syracuse University in 1995. As a result, decisions about rebranding the school’s image and mascot ran into the early 2000s.

For decades the Pioneer mascot was a symbol of Utica College until 2002 when the institution realized that it was racially offensive and politically incorrect. During that time, even though there was no physical image of the Pioneer or costume on campus, it was still the face of the institution. The college began rebranding efforts to revamp its image. The two main mascot ideas that stood out the most were a “raccoon” and an “ox.”

“The narrative of the raccoon being this wiry, quick moving small but effective thing spoke to Utica College,” Lehmann said “We were small, had to respond and kind of had an attitude about us all those things work. The other drawing that they came up with was an ox pulling the pioneer wagon out west. The idea is the big strong thing pulling us forward.”

However, there were concerns that people would refer to Utica as “Coons” or “dumb as an ox.”

“Notre Dame, what are they? They’re the Fighting Irish, their mascot is a Leprechaun. Do you ever call them leprechauns?” Lehmann argued. “What’s North Carolina? They’re the Tar Heels, their mascot is a Ram. Do you ever hear them calling North Carolina the rams? To me, these were all issues that gained some traction and the president (at the time) particularly was worried about these two things.”

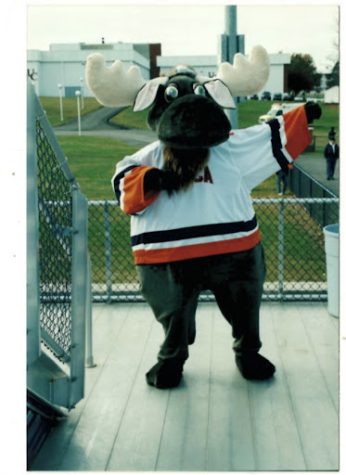

Moose without a name

The moose mascot was born after Jen Hutton, wife of former Utica College President Todd Hutton, bought a book about animals of the Adirondacks, a moose keychain and a moose costume. The moose during that time was indigenous to the area and many thought it would make a good mascot.

On Sept. 21, 2002, Utica College Office of Public Relations sent out a press release titled “Utica College Finds A Moose Without A Name Just Isn’t The Same” to students, alumni, sports fans and community members urging them to submit names to help name the new athletic mascot. The school held an eight-week Name the Moose contest in November 2002 to introduce a new mascot to represent the school not only as the new athletic symbol but also as a physical one that people could see and interact with. More than 200 hundred entries submitted. Some names in the running were James, Fenimore and Cooper to honor James Fenimore Cooper, author of the novel “The Pioneers.”

The winner was announced at the Nov. 9 football game against Shenandoah University. The “Trax the Pioneer Moose” name was given to the mascot by Ric Hollins, a former hockey game clock operator. It wasn’t until the fall 2003 that Trax made its first appearance on campus. Trax was revealed at Homecoming and as the mascot burst onto the field the crowd went into a frenzy. Trax at that moment set the stage and captured the hearts of the community and replaced the Pioneer as the new face of Utica.

Trax’s home

Trax resides in the office of Student Living and Campus Engagement Office as it stores his costume. The moose costume weighs around 28 pounds and like all mascots Trax comes with a height requirement, which stands around 5’8” – 6’. When selecting a person to “become Trax,” adaptability, charisma and energy are some of the main traits they must have since being Trax allows introverts and extroverts to express themselves and do things they wouldn’t normally do.

“It’s not always that we get somebody who is loud, fun, energetic and talkative,”Assistant Director of Campus Engagement Devlin Daley said. “We might get the person who is much shy and reserved but they are able to kind of be the moose. Being able to be expressive without ever seeing the face and taking on the persona of the moose is huge.”

The Trax team has five people in rotation who share the mascot duties. At first, each person is asked to try on the costume to get a feel of how to maneuver and they receive feedback before official duties begin. Because the person wearing the costume can become hot, the average duration someone stays in the costume is about an hour and a half. An ice vest is also strapped around that person to help them cool down.

Becoming Trax

There is only one rule that every person must follow when inside the costume: Trax cannot talk.

The anonymity of the mascot is a key element that ties into its persona because if people know who’s behind the mascot then Trax becomes the personality of that person. Trax is Trax, and not the person wearing the costume.

“It’s a part of our tradition and culture,” Daley said. “It’s something different. If you knew who was in the costume, why would we not just put moose antlers on them? It kind of beats down the charisma, the charm and cartoonish figure that you get out of Trax.”

To this day no one knows the identity of the person actively wearing the costume as it is a secret that leaves the community wondering. Since its debut, Trax is always accompanied by handlers from Team Trax that guide the mascot around campus since the costume causes vision impairment, making someone vulnerable because the person’s only point of view is through the nose of the mascot’s head. Each mascot has to learn hand signals to be able to communicate with the handlers to let them know if they need anything because they cannot speak.

The Trax job isn’t a typical position that would pop up on the school’s standard campus employment portal, and like other schools Trax is a volunteer position for most. Only Trax members who coincidentally work in the SLCE office and qualify for Federal Work Study funding get paid for their mascot duties.

Keeping up appearances

Paul Ward was a typical college student who enjoyed going to hockey games painted out with his friends and enjoying the college experience. Because of his fun and charismatic personality, Ward was approached to be the new mascot. Twenty years later, Ward never thought he would be part of history that moved Utica into a new direction.

“I knew Paul Lehmann because we were the loudest people in the Aud and out of nowhere one day somebody asked me about being the mascot,” Ward said. “I didn’t really know anything about this nor did I know how to dance or do moves but I said sure I’ll do it.”

After agreeing to be the mascot, Ward and Lehmann went on a road trip to Richmond, Virginia in June 2003 for mascot training. Ward had the opportunity to go to the Richmond Spiders and Braves game where he performed in front of a live audience. He described the original outfit as “beer belly moose with a heavy head that was hot and clunky.”

Ward was motivated to put on the costume and take on the persona of Trax because for him it was another way to enjoy college and share school spirit with students, families and kids. However, he spent about one semester as Trax because having that responsibility had some disadvantages.

“It was grueling work, you’re just constantly sweating,” Ward said. “This original costume was heavy, polyester, uncomfortable and then put the helmet on, you sweat out a few pounds in a course of 30 to 40 minutes.”

Like the Pioneer mascot before it, Trax also wore a raccoon skin hat which was ultimately removed. The large headed, big nosed moose quickly became a well-known figure in the Utica community.

The first-ever costume was store-bought and had different jerseys to match the different sports teams on campus. Most of the jerseys didn’t fit the mascot however, the standard uniform for the mascot was the school’s hockey jersey because that was Utica’s most well-known sport at the time. The second costume was made by Sugars Mascots in Toronto, technically making Trax Canadian. At least two females have worn the costume before, one of which was from Maine.

Trax has also made some high-profile appearances, such as joining Bill Cosby on stage at the Stanley Center for the Arts in 2005 during Homecoming Weekend and walking in Utica’s St. Patrick’s Day Parade, America’s Greatest Heart Run and Walk and Boilermaker Road Race. Trax has also been featured on the cover of every Utica magazine since 2006. The moose also went to the Utica College Holiday Brunch once, but the kids were scared so Trax never returned.

There have been three different versions of the Trax since its first appearance; the third version looks a lot different from the original that debuted. It’s head has been updated the most over the years as there have been three different Trax heads and two different full body suits.

“The first one was really kind of fat and dumpy,” Lehmann said. “People referred to him as a couch potato. He was lovable and funny, but for an athletic mascot, probably not what you wanted.”

As fierce as it gets

There are more than 20 men’s and women’s sports in Utica’s athletics program. The institution has a highly competitive athletic culture and as Pioneers, being fierce and aggressive is important. Trax as the athletic symbol some believe doesn’t give off that kind of personality. Dave Fontaine, Utica University’s Athletic Director, said there has never been a complaint about that.

“Nobody has ever come and said I would like to change our mascot because it’s not appropriate or doesn’t fit what we’re trying to do,” Fontaine said. “I think by and large everybody here has embraced it.”

The logo that represents Utica athletics shows the fierce and aggressive moose at first glance. According to Fontaine, the warmness Trax possesses draws younger people towards it.

“I like Trax and the friendly persona that it has,” Fontaine said. “Would it be a bad thing if it was the fierce one? No, but maybe Trax the Moose is the alter ego of the fierce moose that we wear on our uniforms. When you’re on the field and you’re competing you’re intense and when you’re off, you’re having fun.”

It’s approaching 20 years since Trax became Utica’s mascot. The mascot has grown into an integral figure for the city of Utica. Trax appears at athletics and various other school events as well carving out a niche and brightening the experience of others with its comical antics and welcoming personality to become more than just an athletic mascot. Trax has become a figure that students, faculty, staff and the community have formed a connection with.

Lehmann added: “The biggest advantage the moose has is that it is unique; it’s not like anyone else’s mascot.”

Gail Tuttle • Nov 7, 2022 at 9:29 am

Great article. Well written and informative.

Anne Flynn • Nov 4, 2022 at 2:43 pm

Congratulations to Mickale on a very well written article. I am impressed with all of his research and details. I thoroughly enjoyed reading it and learned a lot. The article will be kept in the Utica archives for future researchers. Thank you. Anne Flynn