Lack of diversity in Division III coaching: An examination of race and inequity in UC athletic leadership

May 18, 2021

Despite the NCAA’s best efforts to foster a more diverse, inclusive and equitable environment for its student-athletes, coaches and administrators, some say not much has changed.

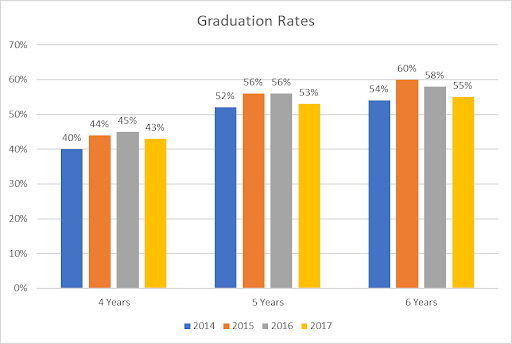

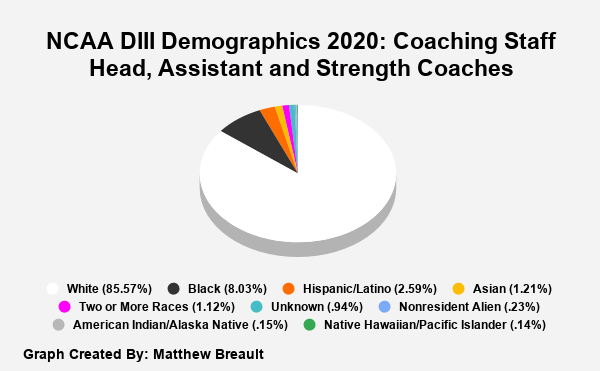

In NCAA Division III athletics during the 2020 academic year, there were 27,842 head, assistant and strength coaches across more than 440 colleges. Yet, only 2,236 (8.03%) were Black, compared to the 23,826 (85.6%) that were white, according to the NCAA Demographics Database.

At Utica College, the numbers are in fact much lower in terms of racial diversity. Out of the 68 paid head, assistant and strength coaches at Utica College, only four (5.9%) are Black.

Recent Posts

- Men’s Hockey Team ready to face off in season opener on Friday

- Dr. Todd Pfannestiel to step down as Utica University president on Dec. 31

- Career Center relaunches Career Closet and plans November networking empowering event

- Dance Night sponsored by Fuerza Latina

- Driven to Win: How Bennett Melita Became Utica’s Top Runner

“I wasn’t really surprised to find out the numbers were so low because for me, I’ve always been the only minority at every university I’ve worked at,” Coach John Boisette said. “That’s just the reality of athletics on a collegiate level.”

All four of the coaches are in assistant coaching roles. Combined, they make up 20% of the Black assistant coaches in the Empire 8 Conference. The experiences these four have are unlike any other of their colleagues. Throughout their lives, they’ve had to deal with various stereotypes and microaggressions that attempt to put them down.

Today, each of these men are in positions of prominence for their respective teams at Utica College. Although the path to success wasn’t easy, each coach has overcome the difficulties associated with being an African American man, and coach, in the United States.

Nick Woodman – Assistant Football Coach – Rovers

Standing at 6-foot-5 and 270 pounds, Coach Nick Woodman’s athletic stature isn’t the only thing that puts him out of place as a coach in the Empire 8 Athletic Conference and at Utica College. His skin color does as well.

Woodman, a native of Utica, spent four years at Utica College playing football and graduated with a degree in public relations, minoring in journalism and concentrating in sports management.

Woodman has had a successful career both playing and coaching football following graduation. After winning the 2019 National Arena League Defensive Player of the Year Award and contributing to the Jacksonville Sharks’ championship run, he signed with the Spokane Shock of the Indoor Football League. Regardless, his successes have come with a plethora of mental health struggles due to the discrimination he faces related to the color of his skin.

“When you’re one of the only African Americans in your position, it definitely begins to affect you mentally,” Woodman said. “Everywhere I go, people look at me differently, especially when I am walking with the shorter white guys on the football team. All the various microaggressions I get for being myself is frustrating.”

A microaggression is a term used to describe an intentional or unintentional statement, or an action that is discriminatory against members of a marginalized group. For example, telling someone they don’t sound Black, calling them the whitest Black person they know or asking to touch their hair are just some of the microaggressions African American people face.

During the summer of 2020, Sports Illustrated asked 14 of the best Black track and field athletes in the United States a series of questions regarding their encounters with racism in America. Each athlete had experienced at least one microaggression while on their rise to stardom.

Grant Holloway, an American hurdler and world record holder who attended the University of Florida, said he was harassed by a family in Florida because of his skin color, his age and where he lived.

“Where I live in Gainesville, is on the wealthier end of the city,” Holloway told Sports Illustrated last year. “One family kept harassing me and asking, Do you live here? Who built your house? When did you buy your house? What’s your address? It was just because I’m a 22-year-old Black male. People think you can’t afford things because of the color of your skin or your age.”

Woodman said microaggressions at Utica College came in sprinkles for the most part and they usually would come from professors that pushed the wrong buttons. He remembered a time when he experienced a microaggression from a white professor at UC.

“I remember one professor told me I looked frustrated and he asked me if I was going to hit him, or brute and ape out on him and lose control,” Woodman said. “I just remember asking myself why do those derogatory words and phrases have to come out of someone’s mouth when describing what an angry Black man looks like.”

Despite the position Woodman was in as either a student or coach, he said it always made him feel more comfortable when there were more people of color around him.

“As a Black person, you feel more at ease when you walk into a room and see more people like you,” Woodman said. “It naturally makes you feel more comfortable.”

Anthony Bierria-Anderson – Assistant Football Coach – Cornerbacks

After moving to Utica from Long Island, Coach Anthony Bierria-Anderson loved every second of his Utica College experience. He graduated with a degree in public relations in 2018 and is currently pursuing a master’s degree in Educational Leadership for Inclusive Classrooms.

Bierria-Anderson discovered his passion for coaching football toward the beginning of his junior year. By his senior year, he would become a defensive intern for the Pioneers. One year later, he would be promoted to cornerbacks coach.

Bierria-Anderson said certain opportunities present themselves elsewhere when colleges would like to add diversity to their staff.

“Coaching isn’t different from any other job for young Black men because it is still difficult for them to get jobs,” Bierria-Anderson said. “We’re also in a time now where things are starting to change and people want diversity on their staff, no matter the profession.”

Bierria-Anderson looks at the positives of the situation, despite being one of the few Black coaches on campus. Since the football team is predominantly Black, according to Bierria-Anderson, it’s helpful for these young men to see coaches like himself. It symbolizes a sign of hope for them.

“Being their role model is a great feeling and you see a difference in how they act and how they respond to you,” Bierria-Anderson said. “I try not to take that for granted because I know I can relate to them on a higher scale than maybe some of the other coaches.”

Tracy Branch – Assistant Football Coach – Defensive Ends

Coach Tracy Branch is the only African American coach that has an additional job on campus. When not on the sidelines, Branch can be found at Utica College’s Office of Opportunity Programs (HEOP), where he is a counselor.

After playing football between 2007-2010 for the Pioneers, Branch has spent the last decade with the team in different coaching roles. Since he is both an assistant coach and college staff member, he sees the lack of diversity from both sides of the field.

Branch said Black men are looked at and treated differently when wearing a polo shirt and khakis, versus a helmet and shoulder pads. Throughout his life, he was taught to ignore the various microaggressions and stereotypes because they’ll always be there.

“As a Black man living in this society, I think you almost have to expect these things to happen because if you don’t, it could really put you down,” Branch said. “I have seen this put people into a traumatic space where they’re unable to function and be their best selves. I think you have to harden yourself around it a little bit just so you could be a well-functioning and participating member of a community.”

Being a member of a marginalized group can be frustrating for many, especially in times where people believe things are changing for the better. Branch stopped letting these negative associations get to his head. Instead, he educated himself on why these things happen.

“The more you begin to understand systematic racism and some of the other issues we have in society, the more you have to understand that in order to change the system, you have to be able to elevate to a certain point,” Branch said. “I learned a long time ago that if I allow every ignorant statement, microaggression or the other variety of things African American individuals have to deal with shake me or put me in an emotional state, then I’m not going to be productive in changing the system and making it better for the individuals coming behind me.”

John Boisette – Assistant Track and Field Coach

Boisette’s road to Utica College was unlike any of his fellow African American coaches. He is the only African American coach who is paid full time, doesn’t coach football and wasn’t affiliated with Utica College prior to his hiring.

A native of East Hartford, CT, Boisette came a long way before he became an assistant coach for the track and field team at Utica College in 2019. While attending and competing in track and field at Eastern Connecticut State University, he earned his bachelor’s degree in physical education.

In the spring of 2017, Boisette went on to coach at East Hartford High School. After that, he spent two years at Regis College in Weston, MA, where he went on to earn a master’s degree in Health Administration while leading the track and field team to multiple championships.

While on a job hunt, he applied to many places and had multiple interviews, but he heard something out of the ordinary.

“I went through the interview process at over 50 different colleges and all of them told me I was young and overqualified for the position,” Boisette said. “They all said I had more time to get a job and it felt weird getting declined for a position when I had my master’s degree at such a young age.”

Boisette said he has been declined at certain colleges in favor of non-minority coaches who are far less qualified.

“In one of my experiences after I got my master’s, I applied for a job where a college was looking for a sprints coach,” Boisette said. “They didn’t end up hiring me, but they hired a former distance runner who only ran for one year of college, and he had no knowledge of sprinting. It didn’t shock me though because he wasn’t a minority.”

When Boisette was a child, he had a public school teacher who told him she didn’t think it was realistic for him to go to college and didn’t give him a legitimate reason as to why she felt that way.

More recently at a Utica College track and field meet, when an athlete brought Boisette over to the officials, the officials told him to go get one the other coaches instead of talking to him about the issue at hand. Boisette said these are just a few of the things minority coaches experience at predominantly white institutions.

The stereotyping and lack of equitable representation doesn’t stop in Utica College athletics, but extends to the representation of the college’s academic faculty and staff members. According to Utica College’s diversity, equity and inclusion statistics, only 12 (2.8%) members of the faculty and staff are Black.

Dr. Anthony Baird, the vice president of diversity, equity and inclusion at Utica College, is also one of the members of the faculty and staff who is African American. Despite the current lack of diversity on campus, Baird said one of the main goals of Utica College’s 2020-2025 Strategic Plan is to develop a more diverse, equitable and inclusive climate.

“The representation of diversity on campus could be better, and we understand that,” Baird said. “When you look at the strategic plan, you can see the status updates and how we are doing in our attempts to become more diverse. It’s important to note that diversity has intersectionality. It’s not only just people of color, but it’s also disabled, gay or lesbian, indigenous and more.”

Over time, professional sports leagues have also attempted to address the lack of diversity in their organizations. According to the New York Times, despite a handful of initiatives meant to increase diversity in the leadership of sports organizations, coaching and management roles have mostly gone to white candidates in the past 30 years.

The most well-known rule in professional sports that addresses diversity came from the National Football League.

The NFL adopted the Rooney Rule in 2003 to promote diversity, equity and inclusion in the sports industry in an attempt to phase out discriminatory hiring practices. This rule states that a team with a position vacancy must interview at least one or more diverse candidates for the position. Despite this, the NFL only has two Black head coaches and 35% assistant coaches represent people of color.

A rule like this in the NCAA could change a lot, according to Boisette, but he said there are other ways to hire more diverse candidates. Boisette suggests that companies should challenge their non-minority employees to find a Black person who they know is qualified for the position.

“It would be interesting if companies challenged their non-minority staff to refer the bosses to minorities who they believe fit the qualifications for the position,” Boisette said. “This way, the non-minorities can’t claim the Black man in a higher position than them is the Black token for the company.”