It’s been six years since New York passed bail reform legislation on April 1, 2019.

Since then, the reform’s impact has coursed through the veins of the criminal justice system.The reform aimed to “advance pretrial justice” by reducing pretrial detention for those who lack access to money, according to a 2024 report by the Data Collaborative for Justice.

However, it has also raised questions about public safety and recidivism, and the reform has drawn criticism for changing how bail worked statewide, including Oneida County. While the reform is “noble in theory,” some officials said discretion is still needed concerning the offense and or individual based on previous acts.

Bail before the reform

Before bail reform took effect on Jan. 1, 2020, there weren’t any conditions for courts to consider setting bail. Courts could set any amount of bail for any charge.

Bail is the money that is given to the court and makes sure the defendant comes back, said John Leonard, a defense attorney at Leonard Criminal Defense Group in Rome.

When a person was arrested, they appeared in court for arraignment. At arraignment, the judge decided that the defendant could be released on their own recognizance without bail. Or, if the judge felt they were a ‘flight risk’ and wouldn’t return to court for trial, they would hold them in jail with or without bail.

The bail is returned after trial if the defendant makes all their appearances and shows up to court.

“If it’s a $1,000 cash bail, and they’re struggling for $1,000… likelihood is they’re probably going to show up because they need that money back,” Leonard said.

However, there were no requirements for what charges a judge could set bail for or how much bail could be set.

Before the change, judges could set bail for “whatever they wanted to,” he said. A lot of times, judges listened to the District Attorney on what the usual bail amount is, but with “no rhyme or reason.”

According to the U.S. Constitution’s 8th amendment, excessive bail “shall not be required.”

“It’s not meant to punish somebody,” Leonard said. “So the judge doesn’t like you because you’re a punk ass to them… ‘Normally, I set $500. I’m setting $5,000 because you’re a punk,’ Can’t do that, you can’t do that.”

Bail after reform

Bail reform splits crimes into two categories: bail-ineligible and bail-eligible offenses.

Essentially, it changed which crimes courts could consider setting bail, said Todd Carville, the Oneida County District Attorney.

Violent felonies, such as sex offenses or domestic violence charges with an order of protection violation, remained bail-eligible. Thus, a judge would have the discretion to set bail for people with these charges.

However, a majority of misdemeanors and nonviolent felonies were made bail ineligible. This means that a judge could not set bail for these crimes. Instead of pretrial detention after arrest, they would get mandatory release, regardless of the circumstances, such as if the defendant had previously committed a crime.

“That’s a big difference is that, like now, most people are released. There’s very few charges that you can get that require to have bail,” Leonard said. “Where before, it was like everything had bail on it.”

Even in cases where judges could consider setting bail, there are further restrictions. Judges are directed to consider “least restrictive means,” Carville said.

For example, they have to consider the defendant’s prior convictions or their personal financial circumstances.

With bail reform, people now have to worry about the individuals who committed crimes being released while the case is ongoing, he said.

“Most individuals are released the day of the incident and are right back in the street,” Carville said. “That has a negative impact on the community for which we’re trying to bring justice to.”

When people see someone who committed a crime walking among them, they believe they weren’t held accountable, he said.

“The issues that communities are having with some of this legislation has given rise to the belief that there’s less punishment for crime,” Carville said. “And that always encourages bad behavior.”

This leads to distrust in the process and fewer people reporting the crimes they see.

“They feel like they were let down,” Carville said. “If they see something a second time, they’re not going to get involved because they’re going to say, ‘What good does that do?’”

Most Oneida County crime occurs in Utica

If fewer people report crimes, it could look like crime is down statistically, Carville said.

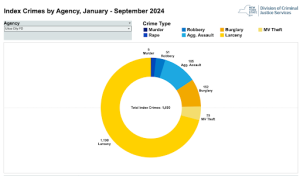

New York State has seven index crime categories to identify crime trends: murder, rape, robbery, aggravated assault, burglary, larceny and motor vehicle theft.

Crime rates are calculated by dividing the number of reported crimes by the population and multiplying that by 100,000.

As of 2023, Oneida County’s Index Crime Rate was 2,034 per one hundred thousand people, according to the New York State Division of Criminal Justice Services. The population count was 228,669 and most of the crimes occurred in the city of Utica.

In 2023, with 3,449 crimes per one hundred thousand people, the city of Utica had the highest crime rate in the entire county. The population was 63,607.

The crime rate dropped to 2,700 crimes per one hundred thousand people in 2024. Utica’s population was 62,571.

“I think it’s a little high for a city our size,” Utica Police Lt. Michael Curley said. “We are an impoverished city with a relatively high crime rate with respect to all part one crimes… we handle it the best we can.”

Curley oversees the major crimes division that handles all major violent incidents. They’ve seen a “precipitous” uptick in juvenile gun violence.

Last year, Utica Police reported 13 shooting incidents involving injury. Six people were killed by gun violence. In the first three months of 2025, Utica has reported three shooting incidents involving injury so far.

With juvenile gun violence driving a lot of the violent crime in the city, another justice system reform, Raise the Age, has driven crime up, Curley said. Before 2019, offenders 16 years of age or older could be prosecuted as an adult.

But with Raise the Age, the range has changed to 18 and older. Now, juvenile offenders younger than 18 get sent to Family Court, where they’re adjudicated and their case is expunged.

By not showing kids early on that their actions have consequences, there’s an “escalator effect.” Local kids are allowed to commit bigger and bigger crimes until they’re 18, and they know they’re not going to be held accountable, Curley said.

“You know, it’s not very rosy in the law enforcement and prosecutorial field right now with respect to trying to hold people accountable for their crimes,” he said.

While bail shouldn’t be a wealthy versus poor economic condition, and everyone should have the same conditions, bail reform took away a “dangerous standard,” Curley said.

Regardless of someone’s criminal history or how many times they’ve committed a particular crime, they get released. Bail is solely for them to return to court, he said. It shouldn’t be used as a punitive measure, and although reform was needed, it also shouldn’t be used as a public sanction for safety.

The reform is “noble in theory,” he said, but judges need discretion concerning the dangerousness of the offense or the individual based on prior bad acts.

“That is the biggest hindrance to successful criminal justice reform, like an individual can commit a very heinous crime, be a danger to the public, and that cannot be conditioned into whether they should be released or not,” Curley said.

No more ‘deterrent factor’ for addicts

Bail reform also affected people who are struggling with addiction and mental illness by changing the way treatment courts work.

Treatment, or diversionary courts, include mental health, addiction and domestic violence court.

These programs have different services and milestones that a person would have to complete in lieu of serving their jail sentence.

Previously, people suffering from addiction knew they could get either go to jail and “get clean” or get diverted into a treatment court, but with bail reform, the sanction of jail is no longer there. It is no longer a “deterrent factor.”

“Now it’s been completely taken away, so I think with respect to petit crimes and drug offenses, bail reform has hurt that population that we’ve seen a precipitous uptick in overdoses,” Curley said. “We are no longer able to hold the criminal justice system over these people’s heads in order to get them the help that they need.”

Mental illness has also skyrocketed, and there are very few services to meet those needs, he said.

Mental health court has treatment services such as court-mandated medication regiments or attending therapy appointments regularly, Curley said. However, it’s difficult to ask them to be independently compliant with these services.

“You have no teeth to have these diversionary courts, so they’re basically feckless because there’s nothing to hold them accountable to doing those steps anymore,” he said. “These people don’t have a facility or support systems and they’re just out in the streets.”

If they didn’t complete the program’s steps, then they would plead guilty to their charge and spend time in jail, where they can potentially take that time to get better, Curley said.

“So you don’t have that anymore. So why would you comply with your treatment? Why would you not use drugs? Why would you comply with your services?” he said. “That’s, I think, why you see a rise in homelessness and rampant drug use.”

Curley said the huge hindrance in bail reform is that it’s “really been a problem” for repeat offenders, also known as ‘recidivism.’

Bail reform and recidivism

Recidivism is the tendency to re-offend after a previous conviction or arrest.

“From day one, there were huge concerns that it would reduce public safety, increase crime, and increase recidivism,” said Rene Ropac, a Senior Research Associate at the Data Collaborative for Justice at John Jay College.

The Data Collaborative is a nonpartisan criminal justice research group that aims to inform policies with data-driven research. DCJ conducts studies on topics such as pretrial justice and case processing in New York State.

Ropac authored DCJ’s 2024 study, “Does New York’s Bail Reform Law Impact Recidivism? A Quasi-Experimental Test in the State’s Suburban and Upstate Regions” which looked at how bail reform played out in terms of recidivism.

With bail reform, public safety was at the forefront of the debate.

“We wanted to feed it with facts because it’s easy to look at individual cases, some of which might be outrageous,” Ropac said. “You know, somebody was released without bail because of bail reform, and then they reoffended and somebody gets hurt or even worse… in a state with so many people, you will always find isolated cases of something bad happening, and you can ascribe it to a policy change.”

Regardless of policy, there will always be recidivism, he said. The question becomes: Did things get better? Did things get worse? Or did things remain the same?

Tracking cases from the beginning of January 2019 to the end of June 2022, DCJ aimed to find out how bail reform impacted recidivism in all of New York State, minus New York City.

According to the study, bail reform reduced recidivism for people facing less serious charges and with little to no recent criminal history. It also increased recidivism for people facing more serious charges and with recent criminal histories.

The study was split into two research groups: mandatory release and bail-eligible cases.

Mandatory release group findings

The mandatory release group is the group of people where bail cannot be set. It was the “most controversial part of the policy,” Ropac said. Almost all misdemeanor and nonviolent felony cases are not bail-eligible.

“We looked at cases where we really wanted to conduct a relevant comparison,” he said. “So we had a pre-reform sample that is individuals who were arraigned in the first half of 2019, and then our bail reform sample, our treatment group, if you will, is people who were arraigned in the first half of 2020.”

Using data from the NYS Office of Court Administration, the study tracked re-arrest outcomes of cases arraigned as early as January 1, 2018. Then, it looked at re-arrest rates for at least two years after arraignment.

DCJ wanted to ensure that the pre-bail reform group and post-reform group were highly similar in charge characteristics, criminal history, demographics, etc. It took charges that were bail-ineligible post-reform and compared them with the same charges pre-reform.

“That allowed us to isolate the effect of bail reform on recidivism as much as possible,” Ropac said.

About 61% of the charges were misdemeanors, and 39% were nonviolent felonies.

The study found very few changes in recidivism for the mandatory release group, and they found “very slight but statistically significant” increases in violent felony (9.5% vs. 8.1%) and firearm recidivism (2.7% vs. 2.0%).

Essentially, people out on mandatory release after reform were one percentage point more likely to get re-arrested for a violent felony or a firearm offense than people held pre-reform, Ropac said.

“That’s a very small effect size, but we’re talking about firearm and violent felony re-arrest,” he said. “So something certainly worth paying attention to even if it’s a small effect.”

The study also broke things down into subgroups, including the person’s charge severity and criminal history, to get more insight.

“So criminal history is a pretty strong predictor of future criminal justice involvement. Likewise, the crime that people are charged with whether it’s, you know, is it a low level misdemeanor? Is it a violent felony? Is it petty larceny?” Ropac said. “Those things matter when it comes to recidivism.”

In terms of charges, eliminating bail was associated with a modest reduction in 2-year re-arrest rates for any charge (42% v. 45%) for people charged with misdemeanors, according to the study.

For people arrested for nonviolent felonies, the study found increases in any re-arrest (39% v. 35%), felony re-arrest (28% v. 24%), violent felony re-arrest (9.6% v. 7.5%), and firearm re-arrests (3.5% v. 2.3%).

In terms of criminal history, for those without recent prior criminal histories, eliminating bail was associated with reductions in any re-arrest and felony re-arrests.

For those with a recent prior, the study showed increases for all four re-arrest outcomes (any, felony, violent felony, and firearm).

There were also significantly higher felony re-arrest rates (49% v. 42%) for people who were released and had a recent violent felony offense.

Overall, the mandatory release group showed less re-arrests for people charged with misdemeanors without a recent prior arrest. However, recidivism increased for people charged with “nonviolent felonies; with recent criminal history; and with a recent violent felony arrest,” according to the report.

Bail eligible group findings

The bail eligible group found no clear effects on recidivism, Ropac said.

Bail eligible is mainly comprised of violent felonies. To study the bail-eligible group, it was split into two research designs: A pre-post comparison and a contemporaneous comparison.

Essentially, the pre-post design compared bail-eligible people released under reform in the first half of 2020 to statistically similar people that had bail set in the first half of 2019 pre-reform.

In contrast, the contemporaneous design compared bail-eligible people who were released and bail-eligible people who were set bail within the first half of 2020.

There may have been a modest increase in recidivism because of release.

The “starkest” increase was for people with a recent prior violent felony arrest and people currently charged with violent felonies with recent criminal histories, according to the report.

Overall, both studies point to the same pattern- Those charged with misdemeanors or nonviolent felonies (ones that are bail eligible) and no recent criminal history were unaffected. Meanwhile, recidivism rates for people charged with violent felonies and for people with a recent arrest increased, according to the report.

Factors that lead to recidivism

“So we saw overall recidivism increases for, quote unquote, high risk individuals,” Ropac said. “That is people who are charged with relatively severe crimes and who had relatively substantial recent criminal histories.”

Regardless of any reforms that took place, based on previous studies, people who have a recent criminal history are more likely to reoffend, he said.

On one hand, release under reform may increase recidivism, Ropac said. There may be a lack of a deterrent effect; people might be more likely to commit a crime assuming they can’t be held pre-trial.

However, on the other hand, release under reform may decrease recidivism because it avoids the “criminogenic” effects of pretrial detention. Criminogenic effects is the idea that incarceration makes people more likely to commit crimes in the future because of the effect jail has on people.

“They might lose their job. They might lose their housing. For example, public housing, if they learn about you being charged with a crime, they will literally kick you out. Not always, but that can potentially happen,” Ropac said.

In another study conducted by DCJ, they interviewed defendants in New York City who told them about not being able to make it to work on time because they were detained pretrial. Consequently, they lost their job.

“They might burn some bridges in the social circle or with the family and because of all these, they’re exposed to other people who are convicted of crimes or who are charged with crimes in jail,” Ropac said. “While at the same time, being isolated from more prosocial contacts on the outside.”

That is why people with no recent criminal history released under reform were less likely to reoffend within two years, he said. With facing the consequences of going to jail and having their life interrupted, they’re more likely to reoffend.

However, even someone with substantial recent criminal history and multiple priors might not have that much of a strong criminogenic effect.

“So for individuals who already experienced incarceration several times, that criminogenic effect is going to be much less strong because any effects that jail might have had on their recidivism pattern, that already took place the first, second, third time they went to jail,” Ropac said.

But on the other hand, incarceration for individuals like that might be more effective. For somebody who has a long criminal history and a history of being arrested repeatedly, being in jail might actually prevent them from committing future crimes, he said.

Recidivism’s role in public safety

But does an increase in recidivism lead to a reduction in public safety?

“Recidivism is only part of it,” Ropac said. “You can also have more first time offenders.”

In that case, recidivism rates wouldn’t change at all, and there would be an increase in crime rates.

“But the reality is that the vast majority of crime is driven by people who already were justice involved in the past,” he said. “So in other words, yes, reducing recidivism in practice has a large impact on public safety because most crimes that are committed are committed by people who’ve committed crimes previously.”

Where did bail reform come from?

Bail reform was passed before Todd Carville became the Oneida County District Attorney, and to his understanding, the District Attorney’s Association was not involved in the legislative process, Carville said. They were not asked for their input on its impact.

“It was basically this is what we’re doing, deal with it,” he said.

After its initial ratification in 2019, the bail reform law underwent amendments in 2020, 2022, and 2023, where in each they made certain cases bail eligible again. For instance, a certain level of a burglary charge or domestic violence offenses that involve the obstruction of breathing.

“There’s been some modifications to it because they realize they went way too far and that it was causing a lot of concern with the public,” Carville said. “It’s still not where it should be, but that’s the problem. When you don’t ask the experts that actually deal with this on a day to day basis how to deal with these issues, and you do it from Albany alone, you don’t understand the practical impact that these decisions make.”

Carville understands that there was need for some changes to certain things, but there needs to be stricter legislation to enhance punishments for “bad behavior,” he said.

When it first came out, media outlets all had something different to report on bail reform when it first came out. Depending on political bias, media outlets were reporting either that bail reform was working fine or that “the world’s ending,” and everyone’s reoffending, Ropac said.

There were reports of crime going up as soon as the first day it went into effect, when crime in New York State had already started increasing in late 2019, he said.

“Obviously, other things happened that are not bail reform, right? COVID, the George Floyd protests,” Ropac said. “So blaming any increases in crime that you see around the time, just on bail reform, is motivated reasoning.”

Three months into bail reform being implemented, legislators rolled out the first amendment on April 3, 2020. Around that time, Gov. Kathy Hochul just took office, and she had a strong interest to respond to voters’ concerns about bail reform’s impact on public safety, he said.

The first amendment to bail reform went into effect on July 2, 2020.

“And around that time, they were like, okay. Crime is going up. We gotta address this somehow. Let’s make certain cases bail eligible once again,” he said. “So it was basically a reaction to public safety concerns and the media narrative of bail reform increasing crime.”

Another problem that bail reform was targeting was that people were frequently getting forgotten about in detention and not being arraigned, Leonard said. Now, a part of bail reform is that in New York State, you have to be be arraigned as soon as possible.

Prior to the change, defendants had to wait to be arraigned until the next day or whenever the judge was sitting in, he said. CAP court, or Central Arraignment Processing, now has a new process where you’re arraigned in less than 24 hours. The law makes it so that now “people aren’t sitting in there for no reason forever.”

That was part of it, yet Leonard said as a criminal defense attorney, he agrees with the concept but doesn’t agree with bail reform.

“It’s stupid. It’s made by people who never practiced law,” he said. “If you are given a break and they let you out on no bail, let’s just say, hey. We’re going to release you. You just make sure you come back here. You don’t show,” he said. “And then once that happens, they come in and appear and then you got to set bail on them and they’re out the door again. I mean, it’s just a never ending cycle.”

You get “one break,” Leonard said. If you go out and commit the same crime, you shouldn’t be out because it shows you can’t follow the rules. You should be required to post bail to make sure you return to court.

The rule goes for everybody, he said.

“You know, I’m a criminal defense attorney, but I live in the same neighborhood as you do. The same community. I don’t want anybody going out and doing that stuff and keep doing that,” Leonard said. “That’s not what it’s all about.”

Where does bail reform stand now, in 2025?

There’s a disconnect that still exists as far as bail reform and understand the purpose of bail, said Maddy Cittadino, a former defense attorney and current prosecutor at the Onondaga County DA’s office.

She was admitted into practice in January 2024, so her experience with bail comes after the reform.

“I don’t think people really understand what the purpose of bail is,” Cittadino said. “I kind of came to that conclusion that they just think it’s a punitive measure.”

Cittadino said with bail, a “justification” should be made just to ensure that it’s not used to preemptively punish the defendant.

People often see it as someone did something bad, so bail is placed on that person. Or the other way where someone did something bad, they’re released, and people think the streets are unsafe.

“Obviously, those concerns in general are valid, but I think there’s just a disconnect as to innocent until proven guilty and the purpose of bail ensuring that you show up to court,” Cittadino said. “It’s not to punish.”

If a defendant doesn’t show up to court, then they get bail set on them. With these consequences, it prevents flight, she said. If the defendant is charged with a crime, they want the defendant to show up to court and address the charges.

The issue with bail was primarily downstate, Curley said. It was based on very small cases where individuals with petit crimes were held in jail for a period of time because they couldn’t afford bail.

“The difference between New York City and upstate is major with respect to the amount of population in jail, the types of crimes being committed,” he said. “So to extrapolate New York City problems to the rest of the state because of a small number of crimes and individuals I think is wholly unfair and we’re certainly feeling the effects.”

Curley said district attorneys, police chiefs and experts in the field weren’t consulted. Local law enforcement has been to Albany three times to talk about reforms, but it’s driven by “downstate money and politics,” and there is “no appetite” to change what legislators have created and “admit mistakes,” he said.

They’re not willing to have the conversation about what will deter crime, he said.

“It’s just that our voice is not as big as the lobby and the other side, right? Money talks and we’re not in the business of particularly lobbying, you know, law enforcement,” Curley said. “There’s very little we’re going to do to change a legislature’s mind who has a completely opposite political view on these topics.”

In terms of population and numbers, “we can’t even come close” to what downstate has. It’s a pessimistic view, he said, but it’s the reality of what’s been going on for the last four years.

Curley doesn’t see much change in the very near future unless people start speaking up more, he said.

“I think until the society speaks up and the community speaks up and says, we’re really sick of the rampant crime. We’re sick of property crimes. We’re sick of this kind of stuff. We’re sick of feeling unsafe,” Curley said. “I think you’ve seen some law changes because the public has spoken up.”