Ben Mehic, Managing News Editor

James Moran stands on the corner of Broad Street and Mohawk Street in Utica donning a camouflaged jacket, torn pants and a limp on his right leg. Moran has been on the streets for decades, hopelessly – as he described it – holding a sign that reads “help.”

Moran, a homeless man, suffers from bipolar disorder and many other mood-related conditions, according to a State University of New York Upstate Medical University dispatch summary from Nov. 17 to Dec. 1. He has been holding the same piece of cardboard for 20 years, but has yet to receive much of the word that is scribbled on the cardboard. The aged army-like jacket hides a bone that has punctured through Moran’s shoulder. His homelessness, though, hides his mental illness like the hat atop his head hides his scarred skull.

According to the National Alliance on Mental Illness, one in five people in the United States suffer from diagnosable mental illness. To put it into perspective, one out of every five people will log onto Facebook at least once in a given month, according to Facebook Inc. While the advent of social media has made it more acceptable to share each other’s lives online, that sort of openness is restricted to those who suffer from mental illness due to negative stigma.

A continued history

The negative stigma behind mental illness rears its ugly head in the lack of care people who suffer receive – either by choice or by the deficiency of help that is available in the decreased funding, poor allocation of funding and number of available treatment facilities.

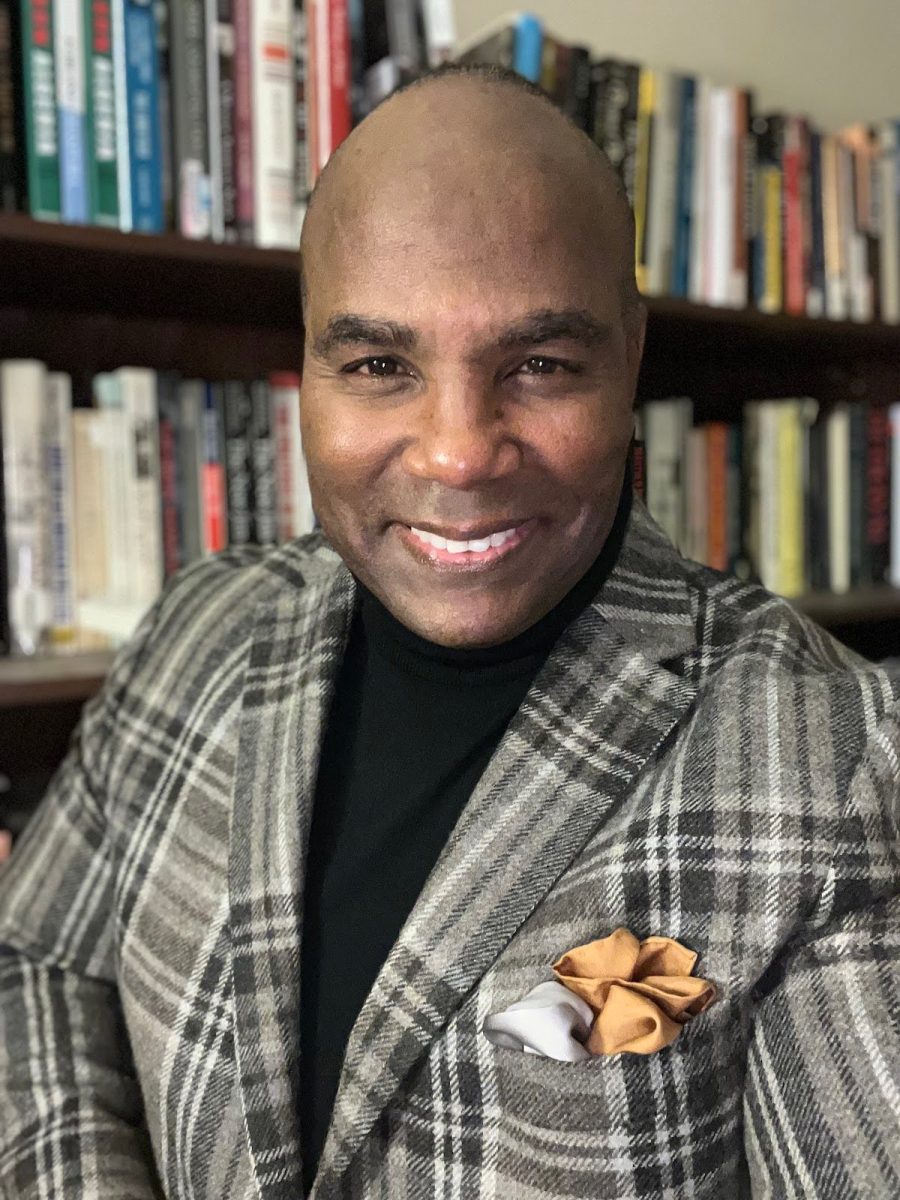

Dr. R. Scott Smith, a Professor of Psychology at Utica College, worked in mental health facilities prior to entering academia and noticed the stigma that is attached to psychological disorders.

“In individualistic cultures, like the one in the United States, there’s a temptation to jump to the conclusion that people do what they do because that’s the kind of person they are. When people are acting ‘weird,’ or they have a psychological disorder, it’s very tempting to jump to the conclusion that that’s just the kind of person they are,” Smith said. “That carries a stigma to it. Some of it is historical and some of it is a byproduct of our default settings that come from our culture.”

Moran said that he was convinced not to seek help for his “personal issues” by his former employer. Even though Moran was influenced into not getting help decades ago, that same type of stigma and lack of attention towards the mentally ill still occurs. According to Connie Everetts, a certified social worker at the Neighborhood Center in Utica, the negative stigma that restricts people who suffer from getting help begins at an early age, often starting with parents of children that have symptoms of mental illness.

“We have to explain to the parents that this isn’t a ‘bipolar kid’ – it’s a kid that has bipolar disorder,” Everetts said. “Sometimes, the parents find it hard to accept that their kid is going to have some struggles that other kids don’t. There’s a level of frustration that occurs with the parent.”

Tom Davison, a peer group advocate at the Adult Recovery Services center in Rome, New York, also battled negative stigma that restricted him from getting help early in his life. Davison, who described himself as a weak and tired man, shook rapidly while discussing his battle with paranoia and schizophrenia. Davison lost his career as an industrial engineer in Virginia because he didn’t seek help. Now, Davison does everything from leading group sessions at the ARS, which is a mental health facility that also treats those with substance abuse issues, to serving coffee at the home-like center.

Davison first experienced his condition in 1976 when he believed he was receiving messages from a higher power. He was hospitalized in 1980 after restricting his diet, experienced a number of setbacks shortly after and ultimately quit his job.

“I kept it a huge secret that I was paranoid. I was afraid if I told people that what I was experiencing would be invalidated,” Davison said. “I bluffed my way through the first couple of episodes.”

After numerous 10-second pauses, Davison opens up about the stigma that stopped him from getting help.

“I had to pretend everything was normal and nothing was happening. I didn’t tell anybody about it. For years, years and years I never breathed a word to anybody,” Davison said. “I didn’t start talking about it until less than 10 years ago. Every time I did put out feelers about things, it was a catch-22. No one believed me – I didn’t think anyone believed me. Or, if I did, I didn’t think they were telling the truth. People weren’t overtly mean to me, but were indirectly mean to me. I thought it was total rejection.”

Consequences of not receiving help

Davison is considerably luckier than Moran and many others that suffer from mental illness. He had numerous people guide him toward situations of recovery and he has since managed to live a relatively productive and functioning life. Others aren’t as lucky.

“The vast majority of people who are homeless either have psychological disorders, substance abuse problems or both. They have been discharged from inpatient mental health facilities and then they go off their meds,” Prof. Smith said. “There’s a lot of human misery, loss of human life, truckloads of money and lots of subtle chipping away at the fabric of the quality of life for people. It erodes certain aspects of life for society as a whole.”

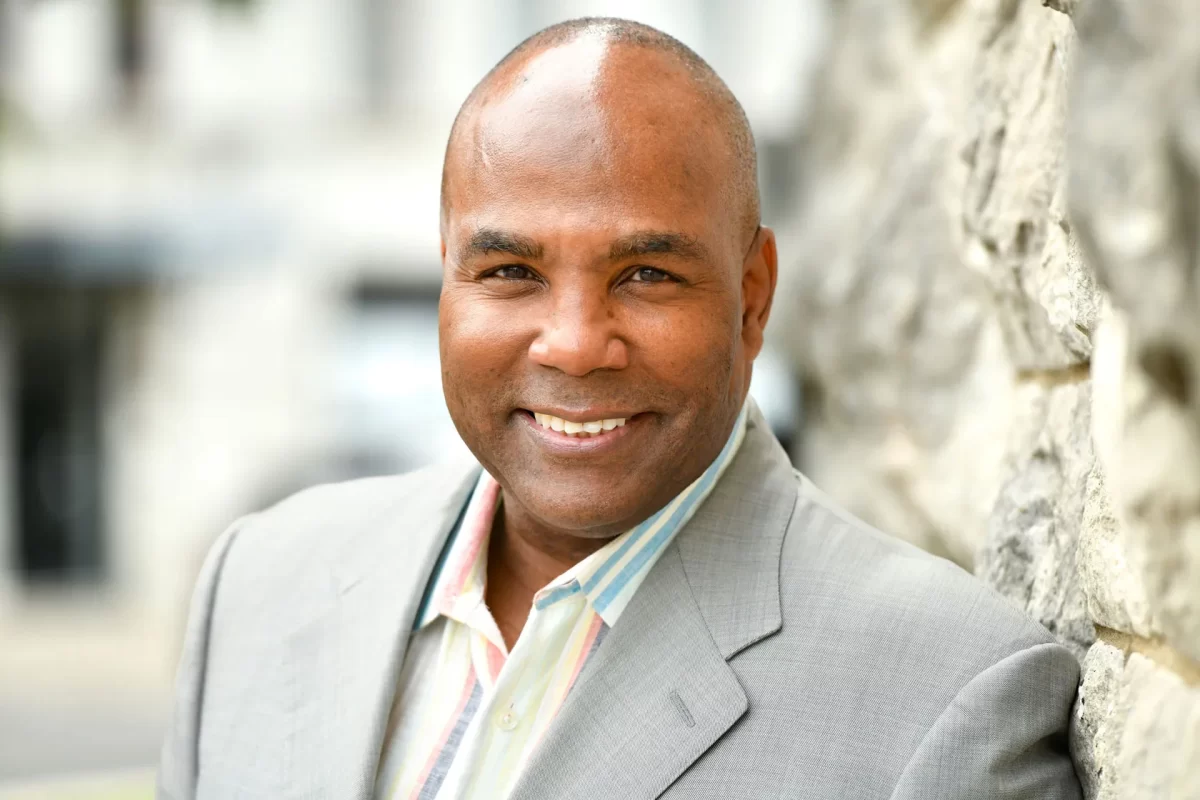

Tom Butler, a Licensed Master Social Worker at Mental Health Connections in Utica – or Human Technologies Corporation – works directly with people who suffer from mental illness and has seen the consequences that those who suffer from mental illness are met with if they don’t receive care.

“A lot of times, homeless people fail to get help, end up in a homeless shelter, don’t take their meds and end up on the streets,” Butler said. “Some people are very hesitant to even take their meds because of the stigma.”

Societal and governmental failures

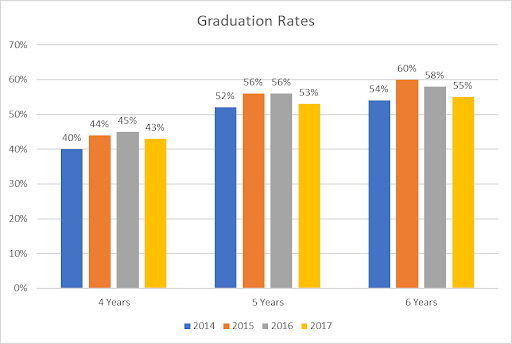

Mental Health Connections has continuously seen its budget decline. In 2006, according to the Oneida County Budget Department, MHC received $447,083. In 2010, it received $342,377. Now, in 2016, the budget has decreased to $135,801. Over the decade-long period, the budget has decreased by 30 percent.

Butler, like many other mental health professionals, has been struggling to adequately provide care that people who suffer need.

“There is less funding. You would have to see a lot more people to get the funding that you used to get, which, is that good care? No – it’s not good care,” Butler said. “It’s all about productivity and overhead. If you have no-shows, you’re losing money.”

Smith also saw the same negative effect as Butler when he worked in the field.

“The best and the most brilliant idea, in terms of mental health, was the Community Mental Health Act of 1965. It never got funded the way it should have. It was something that was designed to help people in their communities,” Smith said. “Most of those programs were based at the county and state level, and they were the first on the chopping block. The first programs that felt the bite were human services programs, like community mental health centers.”

An email to an Oneida County official regarding the funding that MHC received was not returned.

Funding allocation

The Neighborhood Center has seen stagnation in the funding provided by Oneida County, but other places, like Mental Health Connections and the Rescue Mission of Utica – which houses the homeless, many of whom suffer from mental illness – continue to see their primary revenue source decrease.

Between 2014 and 2016, the Utica Rescue Mission lost nine percent of its budget, according to the OCBD. In that same span, the number of homeless people on the streets rose according to New York Governor Andrew Cuomo. While local mental health facilities have struggled to provide care due to lack of funding, the district attorney officials received an approximate eight percent raise in their salary from 2014 to 2016, according to the Oneida County Budget Division. During that final three-year span, from 2013 to 2016, Mental Health Connections lost more than $220,000 to its funding.

Colleen Bottini, the Assistant Director for Behavioral Healthcare at the Neighborhood Center, believes that the “stigma persists and permeates culture, drives funding and causes the public not to demand more funding.”

Although between the ages of 15 and 65, 48 percent of the U.S. population will meet at least one criteria to get diagnosed with a psychological disorder, according to Smith, there is still a feeling that mental illness is abnormal. The unusual feeling that people get when speaking about mental illness starts at home with the parents and restricts those who suffer from getting help, just like it did Moran – and just like it could others.

![President Todd Pfannestiel poses with Jeremy Thurston chairperson Board of Trustees [left] and former chairperson Robert Brvenik [right] after accepting the universitys institutional charter.](https://uticatangerine.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/unnamed.jpeg)